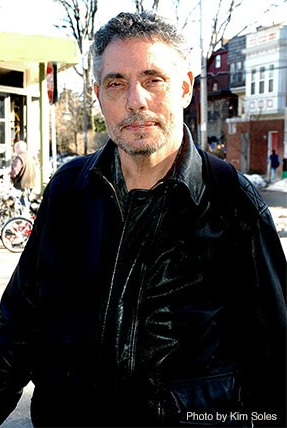

An Interview with Hal Sirowitz

By Mike Cohen

MC: First I’d like to ask your advice on something you and Minter seem to manage very well. How do you find it living with a fellow writer?

HS: It's great. I have a reason to ignore her, and she can't take it personally. “Did you check the eggs?” she'd say. “I'm writing,” I say and everything stops for us, except for the eggs. We both edit each other's work. I encourage her writing. That was how we met, at a writing event. It probably helps that we work on different writing forms. I do mostly poetry. She does non-fiction. To me, one purpose of being a writer is to show others that it's good to express yourself. You create your own personal history by the poems and stories you write.

MC: Did you check the eggs?

HS: Yes, because she was making them for me. I try to help out as much as I can around the house. With my Parkinson's I'm somewhat limited. I'm not good at carrying heavy shopping bags home from the trunk of the car. But I try to make up for what I can't do by what I can. We're going to be the key speakers for a support group of Parkinson's patients in New Jersey. She gets me there and tells what it's like to be a caregiver. We did a presentation at Beth Israel Hospital in New York City that went well. We did one for the University of Pennsylvania hospital all women support group of Parkinson's patients.

MC: Hal, you exemplify making up for what you can't by what you can (to paraphrase your phrase). You and Minter have done admirable things to help others deal with Parkinson's and to show how such conditions can be handled. You manage to find what you can do and use it to good advantage perhaps by doing a greater percentage of what is possible than the average person does.

Sometimes you even use the disadvantages. For instance, when I first saw you perform your poetry I remember thinking how well your dead-pan delivery was suited to your wry, self-deprecating humor. Then I learned that the dead-pan is part of Parkinson's. You made the limited facial expression work in your presentations. (Besides that, you somehow manage to convey an astonishingly delightful demeanor despite the limited facial expression.) What other ways have you turned minuses to plusses?

HS: I've made the audience laugh at my family, especially my mother and father.

My favorite review of my work comes from Norway where a critic said, “You don't have to have a sad childhood to be a writer, but in Mr. Sirowitz's case it helped.”

I became a performance poet even though I was a stutterer and had other speech issues that I had to overcome.

I use silence - those pauses - as an advantage. I draw out the humor in my poems.

I make the audience laugh. I'm saying don't worry if you've had bad relationships, because look at me, I've had bad ones, but I keep going.

I've been lucky to meet you when I first moved to Philadelphia. This interview you're doing is helping me define myself.

We don't exist in a vacuum but in our relationships with other people.

My life has been a struggle against limitations - like the Parkinson's - but it also provided me definitions. I know who I am.

MC: I know who you are; you are one of the most widely respected poets I know. Acclaim in poetry is hard to attain and hard to define, as well. What do you consider to be the definitive moments that have established Hal Sirowitz?

HS: You make me sound like a company on the stock market. I guess I'm defined by my work. I'm always publishing poems in magazines and anthologies. I've liked the movie “Field of Dreams,” which said, build a stadium and people will come. There must be a need for people to read funny sad poems about parents. And, “I get by with a little help from my friends.” People, like you and Leonard Gontarek, Courtney Bambrick, have reached out to me, and either published me, written about me or interviewed me. I was the winner of The Nebraska Book Award 2013 Poetry Book Competition. How that happened was Garrison Keillor liked my work, and must have read more than twenty of my poems on his radio show, “The Writer’s Almanac.” Then, I received a Facebook message from a poet and social worker from Nebraska, Greg Kosmicki, who had a press, Backwaters, heard me on The Almanac, and wanted to publish a book of poems. We put together a book, and won the award. I would say part of my success has been luck. Meanwhile, I'm always working, and producing new poems. My poems still get rejected a lot. I was in a disability anthology, “Beauty Is a Verb,” which got me a lot of readings and exposure. Finally, my Parkinson's was helpful. Mike Northen runs a disability online magazine called Wordgathering. He interviewed and has published me.

MC: You may not be a company on the stock market, but you're a blue-chipper in my book. Your funny sad poems strike a chord for a lot of people, mainly because they are good funny sad poems.

There's no place for poets on the stock exchange. The market is soft and the money is meagre. You have mentioned just a few of the accolades you've received. That always helps. But without the internal satisfaction, we might not bother. What part of the gestalt of poetry drives you on?

HS: What drives me on is writing a poem that will outlive me - people will read it when I'm dead. Expressing myself through poetry. Doing what you are doing with this interview - creating your own form by bypassing the pressures of time. To find a haven for my thoughts. “Killing you loudly with my poem.” When I don't write, I don't feel right. Writing is like breathing - it's something I have to do. It's one of the few ways I have of knowing myself. Poetry is my truth. It gives me a history. I use poetry the same way Proust used biscuits - memories are stored in them.

MC: I'd like to follow your ideas of poetry as haven for your thoughts, your truth, your history. Much is based on your experience. To what extent do you feel bound to the literal truth of the experience that spawns the poem? This is interesting as regards your Mother Said and Father Said series. To what extent did you feel bound to keep to their actual personalities? As you proceeded with the series did you find you had created characters that were variations of your parents, and that you had to keep consistent with the characters to a greater extent than you had to adhere to your parents' personalities?

HS: The early Mother Said and Father Said poems were based on things they actually said. As I got further along in the poems they ended up being things my parents should have said. Yet, I remained true to their personalities. The book, My Therapist Said, is not based on one therapist but includes a few, plus friends who were acting like therapists, giving me advice. At the same time I was working on a series with a working title, Hal Almost Said, where I say things about my childhood I wanted to say but hadn't.

I also wrote a screenplay, so I could have my family interacting together. This was entirely fictionalized. What I am saying is that I write many poems by instinct. They must be true to the way I've portrayed the characters previously. I immediately know when the poem doesn't work. Poems that don't work are mostly mental poems, made up without any basis in fact.

My poems are about my parents trying to protect me from the future, but with not the best results. Only God knows what the future will be. You can't protect someone from the future.

MC: I'd like to ask about your revision principles and practices. How much of writing consists of revising for you?

HS: For revision, time is the best judge. If I still feel strongly about a poem a few days later, I try to publish it. I try to revise while the poem is fresh on my mind. A lot of revision is deletion. You have to make the poem smaller. I belong to an online poetry group called Brevitas in which every two weeks we send a poem of twelve lines or less to be criticized. There are forty members. That helps me shorten my poems. A good poet knows when to stop. What I take out of the poem is just as important as what I put in. One method I developed is starting off with a haiku, and extending it into a poem. My theory is some poems you can't make better by revising. I hope I'm smart enough to know when the poem is good or a fake, like it looks like a poem but isn't. Once my poems are in a book, I won't revise them. Sometimes, I let my wife work with me on revisions. I used to write all my poems by pen, but I find it easier to use the computer, because I can no longer read my own handwriting. The Parkinson's makes my handwriting too small.

I've just gotten a poem I wrote yesterday accepted in an online magazine, The Yellow Chair Review. That poem took me fifteen minutes to write and two hours to revise. It's called “Failure to Fly.” It's part of a series of circus poems I was working on.

MC: You are a master of brevity. A great example is “Who Are We Fooling?”

We end every prayer/ in temple, Father said,/ with the same ending,/ “Amen,” which proves/ that man may have/ the last word but God/ is still the master of silence.

Did you have to whittle that poem down, or did it just come out that way?

Your body of work is growing as we go about this interview. So each question is addressed to a slightly different poet. It's like not being able to step into the same river twice. And yet, you seem firmly centered in your work. You have a consistency of style that says, as you have stated in this interview, “I know who I am.”

Your book Stray Cat Blues has three sections. The first section, Life is Funny, has serious elements as well as humor. The second, Life is Serious, has humorous elements as well as serious. The third, Life Just Is, has both as well. Life is real for you and funny. You always seem to give the reader enough humor to go along with the reality to make it worthwhile.

You mentioned fake poems that aren't really poems. What is a fake poem?

HS: A fake poem is one that hasn't been finished. When I first sat down to write, I wrote poems even I couldn't understand, and thought they must be powerful. They weren't. Part of your job as a poet is to communicate your condensed versions of reality. A fake poem is about something that happened in your mind but not in reality. To write a good poem, you have to write bad ones. I have a history of my life through my poetry.

It's like Zen. You don't have to study all the flowers to appreciate a flower. You could spend all your time looking at just one to get at its essence. Deletion is another way of saying it was said already.

My poem “Who Are We Fooling?” is part of a series of prayers and poems about Judaism. Kafka said writing is a form of prayer. I write similar poems from different angles and perspectives. Some that don't work stay some place in my computer.

I agree that you can't step in the same river twice, but if you give the river a name, then intellectually you can step into the Nile a few times. That's why naming is so important to Judaism. God and Adam named the animals. Poets name our emotions. Audubon, the nature artist, drew pictures of all the birds, because he thought if people knew their names, they'd be less likely to shoot them. Somehow, it worked. People shot down fewer birds.

MC: I heartily agree that writing a powerful piece should not be a matter of stumping the audience, and that there must be a balance of objectivity and subjectivity to make a poem real.

Your poems are accessible yet smart. You obviously gear your writing to an audience. What is the composition of the audience in your head when you write?

HS: I met Mark Lerner, the novelist. He told me there are two types of writers, there are those who write for a small audience of one or two people, and then there are the others, who write for a crowd. I write for all the ghosts who live in my head, which constitutes a crowd. But my work must look good on the page. I take pride in knowing when to use line breaks, and when to start and end the poem. I dislike writers who publish poems without titles, and call them Untitled. To me, the title is like a door of a house. It's the way you walk in. A poem needs doors and windows.

Sometimes my dead parents, friends, relatives are the crowded audience inside my head. Sometimes they are living.

Line breaks are diving boards that get you into the poem. Reading poetry is not like wading, only getting your feet wet, but a process in which you are submerged into the poet's world. Your hair gets wet.

MC: You mentioned that a title to a poem is like the door to the house. Which usually comes first for you - the house or the door to the house? You have to have a pretty good idea what the house is like in order to put a door on it. Do you have the essence of the poem figured out from the start or do you have to fumble around in the dark for a while to figure out the dimensions of the house? Is the door the writer's way into the poem or just the reader's?

HS: I usually have the first sentence in my head before I start composing the poem on my computer. Then, the rest of the poem writes itself or is done instinctually by my unconscious. I let the poem go in its own direction. The title helps me and the reader. Sometimes, I put the wrong door on my poem, and have to replace it with another title. The one rule I have is that the title can't be the last line, or part of that line, because I don't want to give away the ending. I see my poems as a condensed story with a beginning, middle and end. Sometimes, I make two poems out of one - two for the price of one. Or, I'll delete the beginning, and start the poem in the middle. I rarely compose the whole poem in my head. Like today, I had a line, “I had my peak experience on a peak,” but when I tried to play around with it, nothing came that moved me. The poem has to move me somewhat for me to send it out to be published. I think I will delete that line, or use it one day. That's how I work.

MC: Writing seems different to me. It feels like what comes from the unconscious or subconscious is the initial spark. Then I play quite consciously with that spark until I get a conflagration or the spark sputters out. Instinct (or whatever the mysterious source is) starts me up and I think I take over from there. But maybe my sense of taking over is an illusion.

Do you feel you have some control in acquiring the germ of the poem? You do seem to have confidence that your next idea will be there for you. A lot of poets seem to live in fear that it won't. They worry about ”writer's block.” I'm not sure there is such a thing. It may just be an incubation period - part of the process. What is your view on writer's block?

HS: Writer's block is like painting yourself into the corner. You have to wait for the paint to dry before you can take a next step. Writer's block is natural for all writers. Sometimes, you have to stop and take a break. Live with silence for a while, until you can go back to writing. The worst thing a writer can do is repeat himself - write the same poem or novel. Toni Morrison said a writer is only as good as his last novel.

I agree with you. Writer's block is part of the writing process. But I'd argue that writing is partly a letting go of trying to control the direction the poem goes in. A poem is like a child that breaks away from the family. Ann Lamotte says you have to write as if your parents are dead. The poem often knows where it's going despite the good intentions of the author.