Twist #24 (Photo by Daniel Jackson)

the animated tranquility of dennis beach

by David P. Kozinski

Walk slowly past or around a Dennis Beach sculpture and you might feel both stimulated and relaxed. As the eye moves across the segments of “Twist #24,” mounted along an approximately 24-foot length of wall, the repetition and variation of color and shape are exciting and calming. There is just enough repetition to provide a kind of visual vocabulary and plenty of variation to surprise and even jolt the viewer a bit. The work might evoke parts of a skeletal spine that is being excavated from the wall. Each segment offers the same four colors – green, red, orange and yellow – in ever-changing relationships from one end of the work to the other. The overall effect suggests something found in the natural world, re-imagined and then rendered with graceful precision.

Wedge #2 (Photo by Daniel Jackson)

Similarly, sculptures from Beach’s Wedge series, like “Wedge #2” with its yellow, green and pink palette and #s 3 and 4 (seen together in the accompanying image), can appear to emerge from the wall. The seeming juxtaposition of vertical and diagonal shapes, the relationships of which change depending on one’s angle of vision, and the bold, primary and secondary colors both attract and confuse the eye. The repetitions of shape and color balance that stimulation with a kind of serenity.

Drift #24 (Photo by Daniel Jackson)

The undulations of “Drift #24” suggest the movement of water. A red, yellow and orange waterfall cascades down the wall: a familiar natural phenomenon has been imaginatively reconsidered.

When I met with Beach at his Newport, Delaware studio recently I was able to walk right up to wall-mounted works and around free-standing sculptures and pieces hung from the ceiling. When I asked him the correct term for the latter he replied, “The best description might be hanging kinetic sculpture. Mobiles are pretty specific to Calder type balanced hanging sculptures, [or] that is how I take the definition of mobiles (in the art world). No one will likely get locked-up either way – neither term will bother me.”

He works almost exclusively in wood or solid acrylic, using precisely shaped, cut and assembled sections that are then joined with epoxy, connected with dowels or stacked with spacers, e.g.: rubber O-rings on the wood pieces, acrylic pegs on the acrylic pieces. Vertical works can be girded with an aluminum rod in the center for alignment and stability. The results are sculptures in which negative spaces play as integral a role as the three-dimensional objects that stand within or adjacent to them.

As we talked, some of the ceiling-mounted works – #3, #4 and #5 of his Spin series – rotated serenely in the studio light. Then, Beach flipped a switch, the main studio lighting went out, and the artworks were illuminated by small spotlights and black lights. This dramatically changed not only the colors of the mobiles themselves but also the perception of the shadows and projections of light through the transparencies in their components. It was as if sunlight had changed in a blink to moonlight, or to light from an unearthly source. He told me the idea of alternative lighting for the works came when morning light slanted through the studio windows and lit up the acrylic mobiles in a way the overhead lighting did not.

Studio view with Spin #3, 4 & 5 (alternative lighting) (Photo by Daniel Jackson)

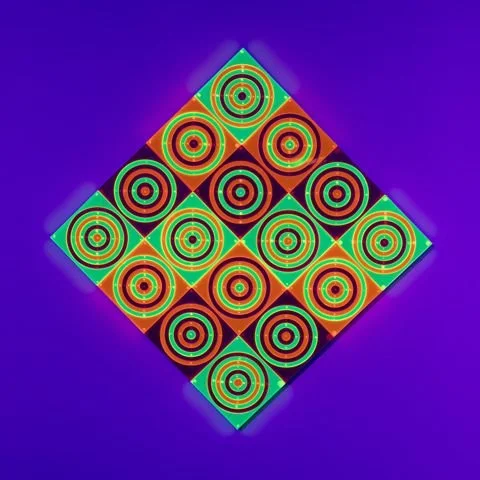

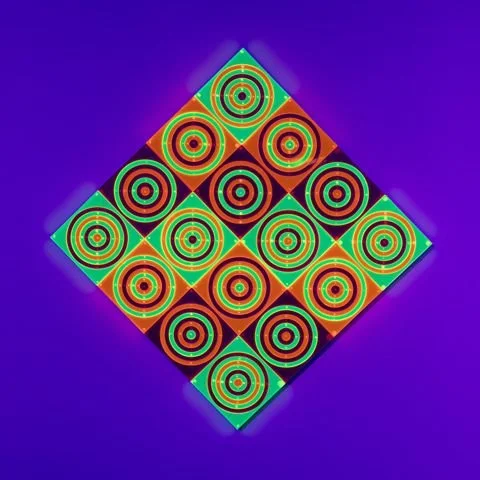

Solar cells turn tiny propellers that keep the kinetic sculptures moving at a pace neither dizzying nor mesmerizing. The effect is both animated and tranquil. Seen in the accompanying images of the kinetic sculptures, placed below them on the floor, lies “Spin #8,” a 45 X 45 inch work of acrylic and stain on plywood. Although part of the same series, this two-dimensional target offers a visual counterpoint to the three-dimensional works above it – a contrast of literal and figurative spinning. “Spin #A-1” stacks targets with several color combinations into a diamond shape. Circles and right angles coalesce, creating a different kind of tension between the surprising and the familiar.

The artist’s parents grew up on the Eastern Shore of Maryland and he fondly remembers boyhood visits to his paternal grandparents’ home – a 250-year-old hotel converted to a house. Some nights he slept on a screened porch, waking with the sunrise. His father was an engineer for the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), which became the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and the Beaches moved frequently, as opportunities for advancement presented themselves. They lived in California, Washington State, Idaho, South Carolina, Connecticut and Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

The family spent Beach’s sixth, seventh and eighth grade years in Japan, where he and his two younger sisters attended the American-run Nishimachi International School in Tokyo. Beach recalls the abrupt adjustment of moving from a typically middle-class life in the U.S. to suddenly going to school with the children of diplomats and AEC officials, and even actress Shirley MacLaine’s daughter Sachi Parker (“Sachiko” as he remembers her). Classes were small – perhaps fifteen students – and classmates’ birthday parties were as likely to be celebrated at embassies as they were at private homes.

Spin #A-1 (Photo by Daniel Jackson)

Japanese culture informs Beach’s sculptures – particularly the architecture with its geometric repetitions – as does the interaction between humans and the natural world. The work also reflects Beach’s desire to recreate some of his responses to the beauty he experienced on the Eastern Shore. Works like “Twist #8” and “Twist #9” bring to mind dream-like tree trunks and the double-helix pattern found in genetics, but also some of the fantastic skyscrapers of Dubai. Another free-standing sculpture, “Curl #4,” can suggest a portal, a stylized alphabet letter, a rollercoaster’s loop-the-loop, or any number of natural phenomena, depending on the angle of vision.

After Japan, the family moved to suburban Washington, D.C. where Beach attended high school. He took wood shop but no art classes. Although he excelled in aptitude tests, he was an indifferent student. College prospects were slim and after graduation in 1974 he went to a military recruitment office where all four branches were represented. “The Air Force was closed, the Army was full and the Marines were scary. My Dad had been in the Navy, so I went for that,” Beach remembers. Again, he scored well on the aptitude tests, was told to return for further testing, and ended up in several Naval training programs in engineering.

Curl #4 (Photo by Daniel Jackson)

He spent five years in the Navy, as a Machinist’s Mate, “monitoring gauges and so forth,” and it was out of boredom that he started drawing. “I took out a five dollar bill and copied Lincoln’s portrait on paper.” Shipmates noticed his skill and paid him to create drawings of sweethearts from photographs. “That didn’t last too long, though. I’d get bored and draw a spider in the girl’s hair, or something, and that wasn’t what they wanted.”

Leaving the Navy, he enrolled at the University of Maryland to study mechanical engineering but after some eighteen months realized his heart wasn’t in it. He went to Montgomery Community College, “to get my grades up and maybe go back to U. of M.” Beach enjoyed studying design and eventually took a semester of art classes, which he continued for two years. These included printmaking, lithography, drawing, painting and photography.

After finishing at Montgomery, the next stop was the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore where he worked on figure sculpture and abstraction. Meanwhile, visits to Washington D.C.’s free museums and the galleries and museums in New York had enriched and broadened Beach’s artistic interests. He recalls seeing one of Ellsworth Kelly’s black and white “curve” paintings and wondering why he loved it. Alexander Calder’s mobiles and other kinetic works of art were another source of inspiration. Beach found himself increasingly drawn to Minimalism. He admires the work of Anne Truitt, known, in part, for her large, geometrically plain and laboriously painted sculptures, like “A Wall of Apricots,” owned by the Baltimore Museum of Art. Truitt grew up on Maryland’s Eastern Shore and spent several years in Japan in the 1960s.

Beach graduated with a B.F.A. and lived in Baltimore for eight years, renting a garage as a sculpture studio and keeping a painting studio in a second bedroom at his apartment. He met his future wife, Toni Vandegrift, when she exhibited some of her artwork in a show in Baltimore. Vandegrift, whom Beach credits with helping make his art career possible, suggested he pursue a graduate degree at the University of Delaware, where he studied with Sculpture Department head David Meyer, among others, and received his M.F.A. in 2005.

At this point he wondered what he would do next, artistically. Early on, he worked with a black, white and gray palette, then added red. He created two large, heavy free-standing sculptures in his garage studio and quickly realized the wisdom of creating works that could be easily disassembled into components and reassembled at galleries or permanent installation sites. All the while, Beach searched within himself, wondering, “What hasn’t been done already? Is there a voice for me?” He concluded that “You can’t escape yourself,” meaning that an artist must please himself first and let the work stand on its own.

Since 2002, Beach has had some sixteen solo exhibitions and participated in many more group shows. His work has been collected by Bellevue Hospital of New York University, the Delaware Art Museum, the University of Delaware’s Museum, and Coventry of Fort Washington, PA, among others. His sculpture “Curve #10” resides at the Comcast Technology Center in Philadelphia. In 2018 he received the Delaware Division of the Arts Established Professional fellowship in Sculpture. He is represented by the Schmidt/Dean Gallery in Philadelphia.

Although Beach’s work can appear playful, its creation requires hours of strenuous calculation, cutting, sanding, and grinding to engineer the desired effects. In recent years, he’s been able to use the Adobe Illustrator program and computer controlled tools, like “CNC” (computer numerically controlled) routers, to lessen his physical exertions. Regardless of technique, the works emanate a combination of the corporeal and the ephemeral that echo the vitality and serenity found in nature. He found his artistic voice and applies it in confident statements that can startle, baffle, but ultimately, please the eye.

David P. Kozinski received a poetry fellowship from the Delaware Division of the Arts and was named 2018’s Mentor of the Year by Expressive Path, a non-profit that fosters youth participation in the arts. He has two full-length book of poems, I Hear It the Way I Want It to Be (2022) and Tripping Over Memorial Day, both from Kelsay Books. He received the Dogfish Head Poetry Prize for his chapbook, Loopholes (Broadkill Press). Kozinski is the resident poet at the Rockwood Museum in Wilmington, DE. He serves on the board of the Eastern Shore Writers Association and on the Editorial Board of Philadelphia Stories magazine.