Art in the Wilderness

In the Northwestern section of Philadelphia, adjacent to congestion, chattering cellphone jabber, and car exhaust, hides an urban sanctuary. Wissahickon Valley Park is a metropolitan jewel where pedestrians and nature lovers escape from the hustle and bustle of city life. It is where my ten-year-old Golden Retriever, Bella, darts up and down hills and jumps into the creek for a swim while I run trails that narrow and widen, drop and climb.

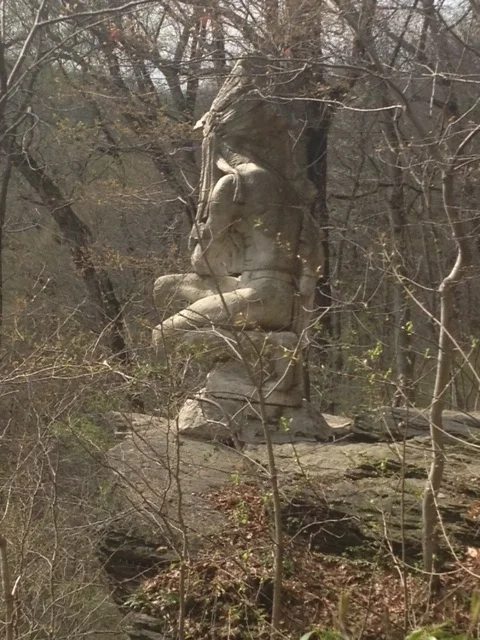

I had run the Wissahickon for years before the day I ventured on a trail not far from my home that climbed, banked to the right and then leveled off. I was in the rhythm of an afternoon run, soaked in perspiration, scanning the view ahead. An opening appeared on my left. I followed steps made of large stone down to a landing, and when I looked up, about twenty feet in front of me on the edge of a cliff, sat a twelve-feet high limestone sculpture, the muscular back of an Indian in full headdress, crouched with his right hand shielding his eyes as he watched out over the Wissahickon Valley.

I shared the story of my finding with a friend, who asked, “Are you talking about Teedyuscung?”

I didn’t know how to respond without sounding clueless, but took a chance and said, “The Indian?”

It turned out we were talking about the same sculpture. She told me that the secluded section of the park is known to locals as Indian Rock, and about the time her son ran away from home when he was a young boy and slept with an Indian named Teedyuscung.

That evening I did what any self-respecting writer would do—I Googled every variation of the name my ear heard—Teddy Uscum, Teddy Euscome, and a dozen other derivatives—before I found a story about a Lenape Indian Chief whose name was Teedyuscung, which means “as far as the wood’s edge.” Teedyuscung claimed to be King of the Delawares and emerged as the spokesman in negotiations with the British for the Lenape to remain in possession of the Wyoming Valley.

After my discovery I learned that the identity of the sculpture is merely local legend. A plaque on Forbidden Drive below on the other side of the Wissahickon Creek reads that the sculpture is meant to symbolize a nameless Indian chief watching his people leave west in the 1750s headed for someplace less crowded. The inscription on the bottom of the sculpture bears no evidence that it is in fact Teedyuscung. But urban legends are like folk tales, they are fun to tell and reveal something about ourselves.

The legendary work was sculpted by Scottish-American sculpture John Massey Rhind, who also created the bronze sculpture of John Wanamaker located downtown in the East Plaza of City Hall at Broad and Market Streets. Tens of thousands of pedestrians pass the Wanamaker sculpture each day. By contrast, there are days barely a creature passes Teedyuscung, except, of course, for a squirrel, rabbit, an occasional deer, or someone like me who stumbled upon the Indian by accident.

Indian Rock is a refuge in city with a population of more than 1,500,000; a place where visitors can find serenity in a breeze rustling through the trees above, and water rushing over rocks in the creek below. Close your eyes and be still with Teedyuscung and it’s easy to imagine the Lenape trekking the woods they once roamed more than a century ago. At times the spot also acts as a sort of community meeting ground for walkers, runners, mountain bikers, lovers, parents with children, and hikers, many with their four-legged friends.

Teedyuscung can be viewed from Forbidden Drive before the trees bloom in the Spring. A plaque just west of the stone bridge at Rex Avenue (there is no sign for Rex Avenue) marks the spot where the limestone structure sits on a cliff 100 feet above on the other side of the creek. Rex Avenue is one mile north of Valley Green, and one mile south from Bells Mill Road. Both locations have parking areas.

To visit Teedyuscung after the robust foliage of Spring arrives requires a hike across the stone bridge from Forbidden Drive and ascending the trail to a path on the left (there is a wooden bridge over a small brook on the right.) The path left to Indian Rock is a long and steep switchback trail. A wooden plank at the first switchback has the word “Indian” and an arrow pointing up carved into it. Continue climbing to the next switchback, and then up even further. Continue walking about fifty feet to the opening on the left, and down the stone steps to Teedyuscung.

The least strenuous way to visit Teedyuscung is to drive west on Germantown Avenue or Seminole Street, make a left at Rex Avenue, and drive to the end of the road where you can park on the side. Walk down the hill to the path, which will now be on your right.

The Philadelphia cityscape is made up of an array of art from the subterranean mosaics along the Broad Street subway line to the sculpture of Billy Penn on top of city hall. But not all of the city’s art is in plain view of the population. In fact, some works require exploration, like the twelve-feet high limestone Indian I found less than a mile from my home.

By Jim Brennan