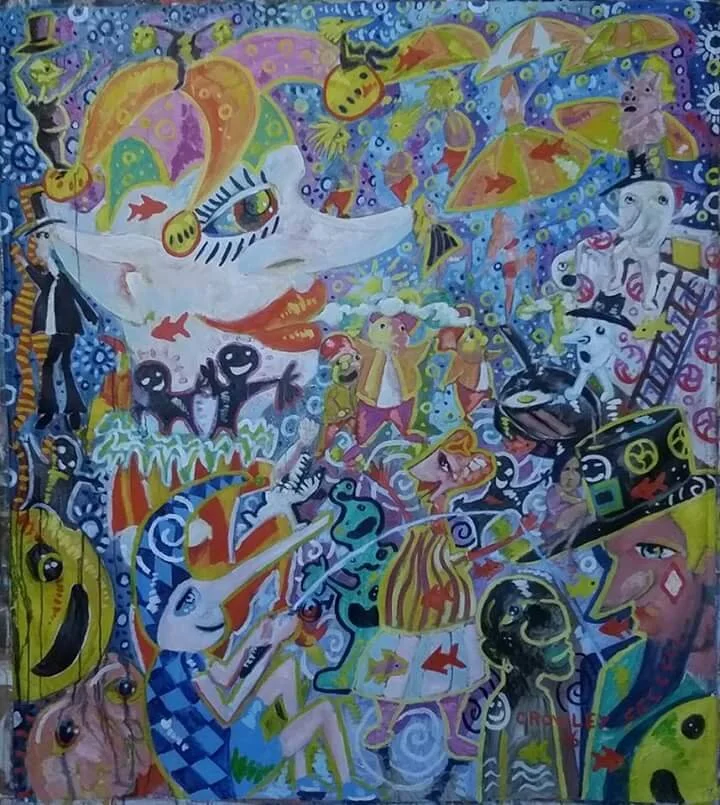

A Jester’s Toast - Dan Crowley

Dan Crowley – A Maximalist Imagination

by David P. Kozinski

Charlotte Rivers, the author of Maximalism – The Graphic Design of Decadence & Excess notes that the movement, “is characterized by decoration, sensuality, luxury and fantasy.” Maximalism in visual art is widely regarded as a reaction to Minimalism, a movement that itself reacted against the gestural work that preceded it. Minimalists such as Frank Stella, Donald Judd and Carl Andre often pared their work down to geometric shapes and monochrome works like Stella’s Black Paintings. The art did not represent something else – a landscape, an object or an emotion – but was to be found in the thing itself. Of his paintings, Stella observed, “What you see is what you see.”

Naturally, with great artists, contradictions are everywhere and plenty of works defy categorization. Although much of Robert Rauschenberg’s oeuvre could not be construed as Minimalist, his White Paintings can be viewed that way. (See Naomi Falk’s article, “Rauschenberg at Play,” in Issue 12 of this publication.) Many of Stella’s sculptures and assemblages are so large, contorted and colorful that there seems nothing “minimal” about them.

Dan Crowley is a painter whose work expands beyond conventional ideas of what a painting is meant to do. His palette is expansive, his canvases packed with commotion and shifting ground. If there is a spectrum with Minimalism at one end and Maximalism at the other, Crowley stands, for the moment at least, near the second pole. He cites Clive Barker’s character development, Mark Messersmith’s “perfect color mixing,” and Stephanie Gutheil’s large paintings with nontraditional subjects as influences.

Crowley also admires the work of Tim Burton, particularly his 1993 stop-motion animated musical film, “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” – from its developed characters and set design to its soundtrack. He asks, “Why shouldn’t all of this be what a painting can accomplish? A good movie entertains…why shouldn’t an art exhibition do the same?” He adds, “The gallery can play dramatic music, have a slide show or movie in the background. Works can be on the walls, on a pedestal, hanging from the ceiling, or on the floor. Guests can dress up in costumes to make the whole experience more interactive. Provide refreshments. Talk it up. And the show could even be filmed. Post it to social media. Make it a party!”

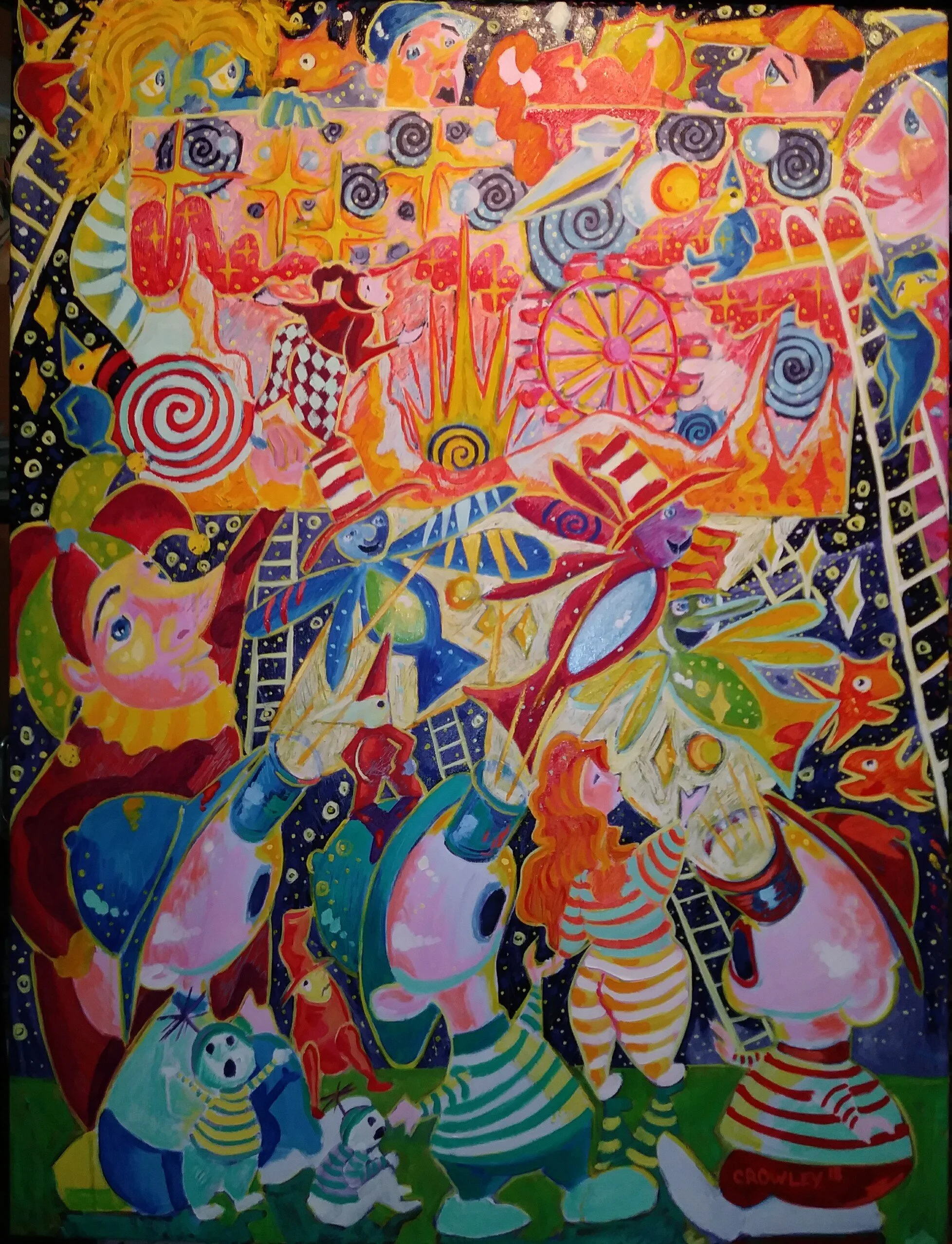

Lights Camera Action - Dan Crowley

Look at just a handful of his busy, colorful canvases, and it is obvious that Crowley is having a blast and wants to maximize the viewer’s experience of his mirth. “A Jester’s Toast” abounds with humor both earthy and ethereal as the viewer’s eyes are forced dizzyingly around the picture. The harlequin-clothed figure, seated with legs open at the bottom left, pops a cork and something fizzy arcs across the scene. Meanwhile, all sorts of jesters and other hilarious characters, depicted in various colors, in varying proportions and in differing degrees of detail, cavort around a clown’s pale face, topped with a fool’s belled cap, which dominates the painting’s upper half. Many of these stylized figures are smiling, but few of these expressions appear simply ingenuous. In fact, a few are all but menacing. Clive Barker, indeed.

Crowley offers stylized human figures in many of his works, including “Lights Camera Action” and “If you believe they put a man on the moon.” In the former, a trio of humanoids whose faces feature spotlights in place of eyes, stand along the bottom of the picture, illuminating the scene above. There, several figures appear to be holding up a backdrop and peeking out from behind it, while others climb ladders or direct the viewer upward. The deep background looks like a starry sky, while in the center foreground, a pair of smiling, flying creatures spread their double sets of wings.

If you believe they put a man on the moon - Dan Crowley

“’If you believe…,’” Crowley recently told me, “really brings together what I’ve been trying to do.” The work borrows a line from a R.E.M. song for its title and presents another sort of Munchkinland, where Saturn glances sideways and downward from a spangled, purple sky. Several black-clad figures, who bring to mind the extra-terrestrials in the neo-noir science fiction film, Dark City,” dominate the center of the painting, although with less foreboding than Mr. Book and Mr. Hand from the movie. The entire picture plane is packed with juxtapositions of color, perspective and telescoping pro-portions.

Currently residing in Woodlyn, PA, Crowley grew up in Brookhaven. He began drawing and painting in 1988 and attended Delaware County Community College before receiving a BFA from West Chester University in December 1994. He also served in the United States Air Force for five years. Crowley has been exhibiting his work at The Blue Streak Gallery in Wilmington DE, where he had a solo exhibit in September, 2018. He was the featured artist last May at the Manayunk Roxborough Art Center (MRAC) in Roxborough PA, and has participated in group shows at MRAC and with the Chester County Art Association in West Chester PA.

Crowley writes, “Although my formal education ended long ago I still consider myself a student.” The internet offers him access to ideas and technical instruction that have advanced his development as an artist. “My teacher is retired professor Gus Sermas (West Chester University) with whom I have maintained a friendship since my college years.” Some of what Crowley told me about his painting process echoes what Sermas has written about his own. “My mode of working is largely improvisational. I often start with a thematic idea and…establish a simple formal outline,” his mentor notes. “From there I make numerous additions with major and minor adjustments. I reserve the right to change any aspect of the painting at any time. It’s important to me that…I preserve the visual evidence of spontaneity.”

Eternal Paradise - Dan Crowley

Only one humanoid figure appears in “Eternal Paradise;” a man in a broad-brimmed hat who seems to pet a cat-like creature that rests on the back of a pig. Another domesticated animal stands in front of them. This Eden, however, is mostly populated by birds – some flightless and some winged. A large web-footed one takes up the center of the picture while monkeys climb a tree behind it, all surrounded by foliage, with a glimpse of outer space at the top.

Motifs like the starry sky, birds, and planets recur in many of these paintings, but each also contains at least one new element. Three trees rise up out of an orb that might be Planet Earth in the center of “Avian Sanctuary.” The trees’ tops have been sawn off, which seems a tad ominous, but bits of foliage sprout from their limbs and birds perch on or flutter around them. An owl flies right at the viewer, freighting its symbolism of nocturnal wisdom and feminine power, its eyes staring straight ahead. Silhouettes of palm trees, another new element, anchor the scene.

Avian Sanctuary - Dan Crowley

Crowley puts cacti front and center in “Desert Dream,” where the night sky’s fireworks compete in explosive energy with the wild foliage below. The succulents populate the foreground of “Southern Siesta,” while a mission, the only evidence of human presence, nestles beneath purple mountains and a sky full of blazing suns.

Although Crowley acknowledges his maximalist inclination, he also refers to himself as a colorist. Paintings like “Celestial Bouquet,” with its striped stems and blooms that emerge like spokes from a coiling, circular figure; and, especially “Cosmic Flowering” and “Dragon’s Dew,” veer toward the abstract. The latter two, while full of suggestive geometrics and symbols, first strike this viewer as studies in color and form before they come into focus as fantasy landscapes. The paintings referred to in this article are primarily rendered in oils, but Crowley has sometimes used combinations of acrylic, crayon (to sketch in preliminary ideas), and fast-drying oil paint. He has recently been experimenting with including fabric in his work and looks forward to doing some sculpture when time and energy allow it.

Like a good poet or storyteller, Crowley leaves ample room in his paintings for the consumer to use his/her imagination. What exactly happened when the tops of the trees were cut in “Avian Sanctuary”? Does the placement of the mission buildings, off to the side and well back, in “Southern Siesta” have a particular significance? Even if he wanted to make such depictions more explicit, the artist’s maximalist approach to subject matter would overwhelm the effort. That we are left to ponder size, spatial and color relationships – let alone “the story” – in each picture, and offered such an abundance of these elements, is much of what makes these works so appealing. As Crowley says, “Make it a party!”

About the Author: David P. Kozinski received the 2018 Established Professional Poetry Fellowship from the Delaware Division of the Arts. His first full-length book of poems, Tripping Over Memorial Day was published by Kelsay Books in 2017. He received the Dogfish Head Poetry Prize, which included publication of his chapbook, Loopholes (Broadkill Press). Kozinski was named 2018 Mentor of the Year by Expressive Path, a non-profit that encourages youth participation in the arts. He serves on the Boards of the Manayunk-Roxborough Art Center and the Philadelphia Writers’ Conference.