By Ryan Latini

I recently came across an 1889 edition of The Prince and the Pauper while perusing a flea market in southern New Jersey. The binding was tattered and it was not a terribly rare edition, but I bought it because I love Mark Twain, not because it was a valuable artifact. It was a treasure of nostalgia for me.

As a teenager, I would have dismissed obvious social commentary as boring and, frankly, easy (I still do today). But lull me into the fictive dream with incredible storytelling, and I’m all ears. When I held that book at the flea market, I remembered the first time in my life when reading became a joyful trip rather than a tedious task—going beyond Tom and Huck in my late teens into Pudd’nhead Wilson, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, and The Prince and the Pauper.

I think that if Twain had not spun these tales in what Robert Regan referred to in “Marking Mark Twain’s Centenary,” first published in the SVJ’s Fall 2010 issue, as “the clarity and freshness of his language and his uncanny narrative genius,” the pure vitriol that became more obvious in Twain’s later years would have kept me out of the world of fiction. Twain could weave in the reality of how things were (are) without ever waking the reader from the fictive dream.

Is that why we still revere the man—because he moved his pen so seamlessly between the waking dawn of reality, so uncomfortable to groggy eyes, and the sweet sleep of tales? Is that why, when the Editor-in-Chief asked for something on Twain, I jumped (much like a certain famous leap frog) at the task? Is that why it felt serendipitous that just a week before I was asked to write this, I had held a copy of a book that existed at the same time as its creator and copyright holder, S.L. Clemens?

Who knows? What I do know is that back in our Fall 2010 issue, during the centenary for Twain’s death, SVJ published a few wonderful pieces on Twain: Robert Regan’s “Marking Mark Twain’s Centenary” and John Timpane’s “I Confess to Being a Twainiac.” We’ve dusted off Timpane’s piece in the hopes that other Twainiac’s will join in our readership.

So why is the white-haired, white-suited, cigar-chomping teller of Americana still so pertinent? Well, you only need to look as far as your television: presidential campaigns, 24 hour-commentary on global atrocities, the ham-fisted handling of (non)issues by our politicians, and the layman’s constant quest for affirmation on social media—the quest for being understood rather than for understanding. We need only to look as far as our critical, typing fingers to see Twain’s relevance.

Or, just look as far as Timpane’s SVJ article "I Confess to Being a Twainiac,” specifically, when Timpane provides a list that shows why Twain’s social judgments were much more nuanced and human than today’s onslaught of constant and obvious social critique that does nothing but fuel our modern quandaries:

“(a) he’s so much like us; (b) he includes himself in the judgment (he’s one of the most self-deprecating writers in history, and holds himself up as an example of many of the failings he decries in American life); (c) ultimately, he is caring and humane (which is why his humor is often so sweet); and (d) he asks the right questions, lancing our racism, materialism, hypocrisy, and nauseating pieties.”

After reflecting on Timpane’s words, and after holding that old copy of The Prince and the Pauper, my takeaway is that to get to the crux of our reality, the only route might be down a twisting, fictive path. Perhaps the tallest tales Twain told enable us to be more honest. Twain’s use of the theme of identity and trading places was perhaps one of his sharpest narrative tools, and perhaps the best lens through which we can honestly look at ourselves. We’ll let Twain hold up the mirror because, as Timpane states, Twain’s judgments include Twain—it’s up to us to look into that mirror and not ignore our own reflection.

I Confess to Being a Twainiac

By John Timpane

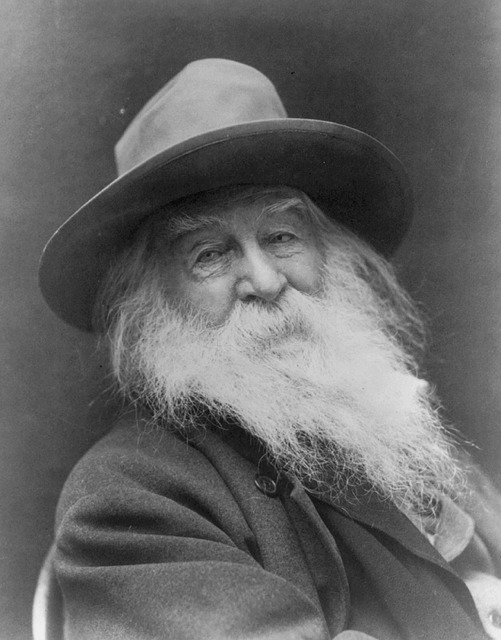

Mark Twain constantly reinvented himself and his art. He was an early master of using what we’d now call modern marketing methods to establish a brand and a public persona. His mane, his moustache, his cheap cigars, all were part of that brand. He first wore his famed white suit, for example, at a 1906 speech at the Library of Congress, and wore it exclusively when he went out from then on.

He tried never to do the same thing twice. True, he wrote a great deal of the Mississippi and life along its banks – but the memoir/travelogue Life on the Mississippi is different from the nostalgic tale of Tom Sawyer, again far different from the dark, mordant Huck Finn. As I write, the University of California Press is about to start publishing the entire Autobiography of Mark Twain. The big news there: he considered the work finished as of 1909, deciding it should be what we’d now call stream of consciousness – a hybrid of diary, autobiography, and dictated whatever-the-hell. No one had ever written anything like it before. Right down to the end, he was inventing new styles, new approaches, new selves.

Which is one of the many reasons U.S. culture celebrates him so. Freelancer, entrepreneur, he’s a self-made man, rising from humble circumstances to world fame – although, let’s face it, he married into money and made the most of it. He’s rooted to our past (born in the slave state of Missouri) and rootless (Mississippi steamboat pilot, failed miner in Nevada, newspaper guy out West, landed Connecticut gentry, world hobo in a global lecture tour to pay off crushing debt, even a couple of years as a gruff resident of Greenwich Village, before dying beneath Halley’s Comet in 1910). Technology mesmerized him, from steamboats to trains to telegraphs to (disastrously) moving type to motion pictures (there are a couple of early, jerky, grainy film sequences of him, but alas, no scratchy Edison rolls graven with his voice). A travel addict, he may have been the most-traveled, best-known person in the United States in his lifetime.

At this writing (2010), the entire country is falling over itself to celebrate Twain from coast to coast. What a summer it has been for Twain fans. Much of this is just good fun. Some of it is our national failing for kitsch, treacle, and cloy. Some is an attempt to display, conspicuously, that we know kultchur. And some is an attempt to put Twain on a pedestal – where we won’t have to think about him.

As I wrote in the Philadelphia Inquirer after my spring visits, he is a strange, not altogether comfortable figure for us to lionize as our great national literary icon. H.L. Mencken wasn’t too far wrong when he said that much of his work was “unintelligible” to the “millions.” There’s a side to him that is not polite, not acceptable. He makes us laugh and invents unforgettable, resonant characters and tales – but he is a stern judge. Take this 1907 note, for a bracing example: “The political and commercial morals of the United States are not merely food for laughter, they are an entire banquet.” As Americans, we hate being judged. But as Shelly Fisher Fishkin, a professor of literature at Stanford, tells me, we let him judge us because (a) he’s so much like us (see above); (b) he includes himself in the judgment (he’s one of the most self-deprecating writers in history, and holds himself up as an example of many of the failings he decries in American life); (b) ultimately, he is caring and humane (which is why his humor is often so sweet); and (c) he asks the right questions, lancing our racism, materialism, hypocrisy, and nauseating pieties.

And so, all cigars in the humidor, our celebration of Twain’s life and work, no matter how uninformed or sentimental it may sometimes be, is a good thing – because it constantly makes us face his astringent and healthy challenge to our facile, self-serving two-facedness.

I confess to being a Twainiac. I’ve hit Twain spots in San Francisco, and in Carson City and Virginia City, Nevada. He was a journalist in San Francisco, indeed, the entire reporting staff of the San Francisco Daily Morning Call, and his daily, on-the-fly, often bald-facedly made-up newspaper stories are among his funniest work. What’s fascinating is that he did not collect it, and many Twain entries may still exist in somebody’s attic or hope chest. Every once in a while, new articles, essays, and speeches turn up.

I’ve visited Mono Lake, California, the site of a miserable visit in Roughing It (“Mono Lake lies in a lifeless, treeless, hideous desert . . .” ). My acquaintance Steve Courtney, publicist and publications editor for the Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, Connecticut, says of Mono Lake: “He’s right — it’s a horrible place, all salt and flies.”

I’ve had (and recommend) pancakes at Gold-Rush-era Murphys Hotel in Murphys, California, where he (and, at another time, Ulysses S. Grant!) signed the register. Maybe he had pancakes there, too. (Personal snapshot: my friends and I sat around the table at Murphys and started to reminisce about the lives of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. Friends Nancy Marks and Maureen Grady burst into tears: “They were so beautiful!” It was like a scene out of Sleepless in Seattle.)

I’ve seen Jackass Hill near Columbia, California, where Twain is said to have heard for the first time about the goldminers’ practice of wagering on jumping frogs. That planted the seedling of “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” and began his career as a nationally known writer.

And yes, I’ve journeyed to Angels Camp, California, and jumped a frog at the festival. I was a terrible frog-jockey; only a single fat, algae-backed bullfrog of mine ever bested ten feet (absolutely pathetic), most of them choosing to ignore my bootless hooting and waving, as the crowd bellowed in laughter. The first year I went, 1975, we entered Angels Camp at around midnight, Hell’s Angels motorcycles lining one side of the street and flashing police cars lining the other. We read “The Celebrated Jumping Frog” aloud at the foot of the Mark Twain statue in Utica park, a ritual repeated in coming years.

And I work at the Philadelphia Inquirer, where Twain was a graveyard-shift typesetter for a few months in 1853-1854, writing amusing letters to his family about how much more he liked Philadelphia than New York, and how drunken much of the Inquirer staff was.

Haven’t gotten to Hannibal yet. But when I drove into Elmira, New York, in the spring of 2010, I saw the Mark Twain Hotel, the Clemens Center Parkway, and Twain himself in an art montage at the entrance to the town. I visited Elmira College, home of the Center for Mark Twain Studies. On campus is Twain’s famous study, octagonal, windows on all sides; his sister-in-law, Susan Langdon Crane, is said to have built it to recall the pilot house of a steamboat. It wasn’t originally there, but a couple of miles away, up in the hills, at the Cranes’ house, Quarry Farm. Susan and husband Theodore, who were childless, invited Twain, wife Olivia, and family to summer there, and they did, from 1874 into the 1890s. Twain enjoyed a steak breakfast, we’re told, then took the short walk to his study, built away from the house, lore has it, because Susan hated the smell of his cheap cigars.

So I got a chance to stand in the structure in which Twain spent summers drafting tales of Huck and Tom.

Later, I stood on the porch of Quarry Hill, where of an evening Twain read aloud to the family and staff from what he’d drafted that day.

On the same trip, I visited his massive house in Hartford, a temple to conspicuous consumption, to view his beloved billiard table, built on the top floor, as he wanted it … and a modest little table in the corner, where he did his writing (instead of in his office, which his wife Olivia had designed for him).

My conclusion: A huge effort goes on every day, across this country, to keep this man and his vibrant, true work alive. We’re not going to let him go.

A Note About the Author: JOHN TIMPANE is Books and Fine Arts Writer/Editor at The Philadelphia Inquirer. His poetry has appeared in Painted Bride Quarterly, Per Contra, Wild River Review, and elsewhere. His books include (with Nancy H. Packer) Writing Worth Reading (NY: St. Martin, 1994); It Could Be Verse (Berkeley, Calif.: Ten Speed, 1995); (with Maureen Watts and the Poetry Center of San Francisco State University) Poetry for Dummies (NY: Hungry Minds, 2000); and (with Roland Reisley) Usonia, N.Y.: Building a Community with Frank Lloyd Wright (NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2000) and a book of poetry, Burning Bush (Ontario, Canada: Judith Fitzgerald/Cranberry Tree, 2010).