Happy Birthday, Billie Holiday: Celebrating Lady Day's Centennial All Year Long

By Jennifer Doerr

Billie sings and I cry. I sit at my desk at The New School Jazz office in New York City where I work as Executive Assistant to the Dean. Through the ear buds attached to my computer speakers, Billie Holiday is coaxing my tears with her plaintive voice, so intimate, like she is my old friend. “Love is funny, or it’s sad/or it’s quiet, or it’s mad/it’s a good thing or it’s bad/but beautiful.” I click the pause button on the album Lady In Satin and hustle to the bathroom before anyone catches me weeping.

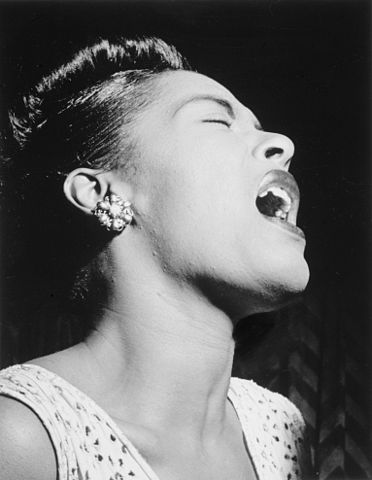

No jazz artist makes me feel like Billie Holiday. Especially when she sings my favorite love song, “But Beautiful.” Billie’s voice is as indelible to jazz as her iconic image: head thrown back, white gardenias pinned in her hair, eyes closed, red-hued mouth open, and that beautiful face that seems to have a source of light behind it. At the height of her career, she was radiant. Billie was an impeccable creator of story through music, styling her phrases with conversational lilts and dips, matched in performance by wide, playful eyes that expressed a happy resignation to heartbreak. Her voice knew things. Things a woman wouldn’t have otherwise been able say out loud in those days. I like to think of her work as the personal essay in song. She doesn’t solve life’s problems or pose answers, but instead lays everything out in front of the listener for observation, without apology. This is what I love about Billie’s music. And so, even if I am a few months late to the party, I want to say Happy Birthday, Lady Day, and thank you for all the years of sweet tears.

Billie was born Eleanora Fagan on April 7, 1915, in Baltimore, and rose to become one of the most important jazz vocalists in history. Her birthday centennial has recently been celebrated by the jazz community and the world. April’s issue of Vanity Fair presented a black-and-white spread of Billie’s personal and public photos. Jazz vocalist Cassandra Wilson released a tribute album to Billie this year, Coming Forth by Day, reimagining the Holiday songbook. And just last year, Audra McDonald channeled Billie in the Broadway play Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar and Grill, which earned her a record-breaking sixth Tony award. McDonald’s performance was so startlingly accurate that, listening to a recording with eyes closed, it is almost impossible to distinguish her voice from Lady Day’s.

In my nine-to-five job as a jazz secretary, I’m called “Lady J” by my bosses, part joke and part flattery, since I sing in church on occasion. At first I was pleased by the nickname, until I learned that another secretary, whose name also begins with “J” was once called “Lady J,” too. That broke my heart a little bit. Having a jazzy nickname is an honor, especially one akin to Lady Day, that name bestowed upon Billie by her dear friend and tenor saxophone player, Lester Young. In turn, she nicknamed him “Prez.” In her autobiography, Lady Sings The Blues, as told to journalist William Dufty, Billie explains the unique closeness of their platonic relationship and what Lester’s nickname signified: “I always felt he was the greatest, so his name had to be the greatest. I started calling him the President.”

Despite my punny nickname, I only have a few minor things in common with Billie. I was born in Baltimore, and have been singing since I was a kid. My mother, who grew up in East Baltimore like Billie, spent many hours scrubbing white marble steps for a quarter a stoop in the fifties, as Billie did for a nickel a stoop in the twenties. And both Billie and I have struggled in relationships with terrible men. In her woeful tune, “My Man,” Billie sings, “He isn’t good/he isn’t true/he beats me, too/What can I do?” How I understand these lyrics all too well, and how I have asked myself the same question. But apart from these things, our lives diverge. I’m a white woman who was born into a privileged life, though one of financially modest means. Billie was born sixty-three before me, an African-American in a segregated America, the great-granddaughter of a plantation slave. As a girl, she was separated from her mother, who supported herself by working as a maid up north in New York City. She had almost no relationship in childhood with her father, the guitarist Clarence Holiday. After the fifth grade she did not return to school and struggled to gain a foothold on success, even resorting to prostitution for several difficult years.

“Sure I can sing, what good is that?” she told the piano player on her first audition in New York. Singing wasn’t something that Billie set out to do. It was a survival job. She was looking for work as a dancer, but was terrible at it. So the piano player asked her if she could sing instead. “I had been singing all my life, but I enjoyed it too much to think I could make any real money at it.” Her audition clearly went well and, after adopting the stage name “Billie” from actress Billie Dove, she went on to cut her teeth singing in jazz haunts like the Hotcha Club, The Log Cabin, and the socially progressive Café Society, where her signature protest song “Strange Fruit” was born.

My good friend Charli Persip, a New School faculty member who toured with Dizzy Gillespie’s big band in the fifties, remembers playing with Billie at the New York Jazz Festival on Randall’s Island. Charli was still a young cat then, and wasn’t used to playing with such big names. “I was in awe,” he recalled. “When I met her, I thought, ‘Oh my God!’ She was cordial to me, but also very serious.” Billie’s manager had reached out to Charli when her drummer couldn’t make the gig, and he, of course, said yes. But there were problems. “I never played with anybody like her. She sang way behind the beat, and I don’t think she cared for me at all. It was a disaster. Not fun.”

Billie was known for being coarse, occasionally difficult to work with, and even violent at times, which may have been the result of her well-documented drug and alcohol abuse. But her autobiography also shows the lighter, more humorous side of this multi-dimensional woman. Lady Sings The Blues’s matter-of-fact recollection does not match up with the tidy 1972 biopic of the same name starring Diana Ross, which memorialized Holiday in a sanitized version of her own life story (Ross’s acclaimed performance earned her an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress). The film details Billie’s tour with a Hollywood version of Artie Shaw’s group as the first black female singer hired by an all-white band, of which she writes, “Don’t tell me about those pioneer chicks hitting the trail in those slip-covered wagons with the hills full of redskins. I’m the girl who went West in 1937 with sixteen white cats, Artie Shaw and his Rolls Royce—and the hills were full of white crackers.” The camera doesn’t shy away from the racial brutality she experienced, but waters down Billie’s defiant nature and shadows the devastation of her heroin use. It also leaves out other touchstone relationships she formed with jazz greats like Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Cab Calloway, Lionel Hampton, Coleman Hawkins and a host of other musical and artistic contemporaries. The good that came out of the film version of Lady Sings The Blues was that it succeeded in bringing Billie’s songs, through Ross, to a broader American public and reawakened an interest in her life. “Strange Fruit,” “Fine and Mellow,” “Lover Man,” “Ain’t No Body’s Business,” and Billie’s seminal classic “God Bless The Child,” are all part of the soundtrack, along with dozens of other Holiday tunes.

I admire anyone who can do what Billie did so well under her circumstances, even when strung out and sad, with chaos running through her veins. I can barely write a sentence in a stupor, and singing a few bars of a church hymn can be a strain when I’m so much as hung over. But Billie’s voice pushed on past itself, transcending her personal demons. The world-weary, congested rasp she acquired heightened the emotional intensity of her songs in her later albums, like my favorite, Lady in Satin.

Billie Holiday died on July 17, 1959 at age forty-four. She succumbed to the drug and alcohol abuse on her body, unable to find the balance between both the structure and the freedom needed to create a happy life. Ironically, it is the same balance of structure and freedom necessary to create great jazz music. Leaning only on the pleasures that surrounded her caused heartache, but in that heartache she was able to dip deep into her pain and understand it, to burrow her way into its tender center and fully surrender. With her, I like to surrender. I think of her anthem, “God Bless The Child,” as a song written by her older self to her younger self: “Mama may have/Papa may have/but God bless the child who’s got his own.” Billie finally got her own; she made it her own, her way. I salute Billie in her centennial year her for the all joy that she has brought me through her music, even as I cry in the bathroom at work.

A Note About the Author: Jennifer Doerr is a jazz amanuensis living in New York City. She earned her MFA from The New School, teaches writing to high school students, and has mentored with the Girls Write Now organization. Her work is published in the Girls Write Now Voice to Voice Anthology, A Quiet Courage, and is forthcoming in The Tishman Review. She blogs at wordandservice.wordpress.com.