Encountering Cioran

By Daniel Lawless

As with so many things – films, cities, bourbon – there are writers one comes to too early or too late. In the latter category, I would include, oh, Salinger, Mailer, Saint-Exupéry, the usual suspects; in the former, Sartre, Bernhard, Coetzee – and Cioran.

A chronic truant and general miscreant in my adolescence, nevertheless I was a reader – if an undisciplined one. Long afternoons at the Louisville Public Library, which seemed to me then at once forbidding and enchanted – a great grey castle-like building with tall windows of cylinder glass. Sometimes I’d come with a recommendation in hand – one author alludes to another, or a name pops up in an index. Mostly, however, I’d leave it to chance: head to Literature, or Poetry, or Philosophy, and find whatever I’d find. So it was I arrived at Cioran’s doorstep, at age seventeen. I remember the encounter almost perfectly. For some reason, I’d paused at the “French” section – not that I could read a word of the language; no doubt I recognized a few names I’d perused in translation: Artaud (The Theater and Its Double), Cendrars, half a dozen of the Surrealists. Then, Précis de decomposition. To an alienated (!), cynical, self-absorbed (is there another type?) teenager of a literary cast, the title alone, with its air of ghoulish academe: catnip. Nor was I at all disappointed when I flipped through the pages, finding now under the heading Certains Matins,

“ Regret de n`étre pas Atlas, de ne pouvoir secourer les épaules pour assister à l’écroulement de cette risible matière…” [i]

(Yes! Hadn’t I too, longed to shake off this stupid world? That sentence alone took me ten minutes to decode, with a French-English Dictionary.)

Now, “Quand on ne peut se deliverer de soi, on se délecte à se dévorer.” [ii] (I had already been diagnosed with an ulcer; it would burst and nearly cost me my life in a few years.)

Picking up another book, Syllogismes de l'amertume, there was this felicitous observation:

“L’odeur de la créature nous met sur la piste d’une divinité fétide.” – a foul God, as foul (and omnipotent) as I knew myself to be! [iii]

And so on.

Disappointed? How could I have been? Listen to Kimball’s 1991 dismissal of Cioran in The New Criterion: “…a style [italics mine] that blends an almost Olympian coolness and intellectuality with the appearance of passion bordering, at times, on hysteria…essentially an adolescent style: high-handed, confessional, histrionic, but nevertheless full of energy.”

Well, yeah.

So, in one sense not too early: for even if that “reappraisal” were altogether true, didn’t Cioran give me exactly what I needed, then? What Kerouac, Ginsberg, Warhol, Johnny Rotten have always given to their fans – a vision or version-presentation of their own Weltanschauung – though they might not know they had one? A glimpse of what their own stylistic preferences might comprise; mirror in which they might find themselves reflected for once, perfected, their inchoate rage and limpid yearnings legitimized, even encouraged?

But it isn’t, is it? True, I mean, Kimball’s assessment. At least not altogether. Isn’t it also possible Sontag was right, that Cioran’s

“…kind of writing is meant for readers who in a sense already know what he says; they have traversed these vertiginous thoughts for themselves. Cioran doesn’t make any of the usual efforts to “persuade,” with his oddly lyrical chains of ideas, his merciless irony, his gracefully delivered allusions to nothing less than the whole of European thought since the Greeks. An argument is to be “recognized,” and without too much help. Good taste demands that the thinker furnish only pithy glimpses of intellectual and spiritual torment. Hence, Cioran’s tone—one of immense dignity, dogged, sometimes playful, often haughty. But despite all that may appear as arrogance, there is nothing complacent in Cioran, unless it be his very sense of futility and his uncompromisingly elitist attitude toward the life of the mind”?

And if she is correct, and I think she is, then, in a more profound way, I was indeed too early – far, far too early, as I have learned over the half-century since. I simply had not read enough to capture a tenth of Cioran’s allusions, let alone decipher his relentless, playful paradoxes. To say nothing of appreciating his exquisite, yes, style.

So, split the difference – too early, but also right on time.

For the moment, let’s return to that long-ago boy, that long-ago library. Four books in all, including La Tentation d'exister, and De l'inconvénient d'être né. I must have remained entranced there for a good eight hours, on the floor with its ancient stained scarlet carpet (coffee, and were those cigarette burns?) until closing time, shifting my attentions from one book to another dictionary in hand, when I noticed it had grown dark. Gathering my bounty, I paused to peek at the little sign-out sheet under each cover, wondering what kindred spirit might have walked these same purgatorial alleyways before me. Virginal. Not one had been checked out. I knew what I had to do.

In those days, of course, there were no detectors stationed at the massive oak doors that faced the check-out desk to alert absent-minded patrons of their clerical requirements – or nab would-be thieves. So: out I went, my army coat pockets rather heavier than when I had entered.

(Would he have approved? I was certain of it. Just as, a few months previous, I had taken Merton for a rebel; before that Husymans a traitor.)

At home that evening, and for many evenings to follow, I could be found (by whom? a figure of speech; I was an isolate by decree, as C. says somewhere), poring over the work, line by line, word by word, with that trusty paperback Webster’s. Cioran became the first writer whose entire oeuvre I read – those in French as well as Richard Howard’s marvelous English translations. Nor has my enthusiasm, tempered by age as it might be, waned in any substantial way. (I have read and read him again, and again, as some their Bible or their Pynchon. A 62 year old fan boy.)

Tonight, as I write these few words, his face – that Bernstein-ian countenance with its unforgeable signature of suffering and intellect – is propped against the wall behind my desk. An insect, almost imperceptible, a moving virgule, traverses his cheek – without thinking I reach out to extinguish its life as one would a match-flame. Instantly, regret. Not for it but for me. L’acte Cioran-esque, let’s call it.

A Note About the Author: Daniel Lawless’s book, The Gun My Sister Killed Herself With and Other Poems is forthcoming from Salmon Poetry, February 2018. Recent poems appear or are forthcoming in The American Journal of Poetry, Asheville Review, Cortland Review, B O D Y, The Common, FIELD, Fulcrum, The Louisville Review, Manhattan Review, Numero Cinq, Ploughshares, Prairie Schooner, and other journals. He is the founder and editor of Plume: A Journal of Contemporary Poetry.

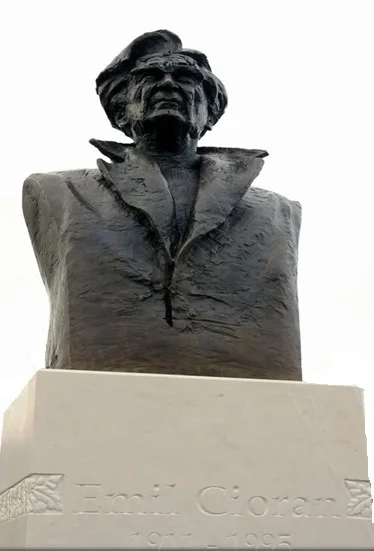

Emil Mihai Cioran,1911-1995, was Romanian-born writer who was the author of elegantly written philosophical essays in which he displayed a sense of alienation and pessimism that was, according to one critic, "so profound and ironic as to almost meet a serious optimism at the other end of its arc." Cioran received a degree in philosophy (1932) from the University of Bucharest, having written his thesis on the French philosopher Henri Bergson. His first book, Pe culmile disperarii (1933; On the Heights of Despair,1992), won a prize for young writers from the Romanian Royal Academy. Over the next four years he studied philosophy in Berlin, taught briefly in Bucharest, and wrote three more volumes of essays. In 1937 Cioran went to Paris on a grant from the French Institute in Bucharest. There his philosophy of futility and despair found a suitable home among French existentialist and nihilist writers. He lived in Paris for the rest of his life and wrote 10 books in French, beginning with Précis de décomposition (1949; A Short History of Decay, 1975). Later books include La Tentation d’exister (1956; The Temptation to Exist, 1968) and De l’inconvénient d’être né (1973; The Trouble with Being Born, 1976).

Special thanks to John Taylor for confirming the accuracy of Lawless’ translations of Cioran.

Born in 1952, in Des Moines, Iowa, John Taylor is an American writer, critic, and translator. He studied mathematics at the University of Idaho (graduating in 1974), then literature and philosophy at the University of Hamburg (Germany), where he was a Rotary International Fellow. He also spent a year on the island of Samos, Greece, before settling in France in 1977. After living in Paris until 1987, he moved to Angers, in the lower Loire Valley. Taylor is the author of seven collections of stories and short prose, six of which have been translated into French and two of which into Italian; selected poems and stories have appeared in Dutch, German, Greek, Polish, Ukrainian, and Slovene literary reviews. As a polyglot literary critic, Taylor is one of the most active “passeurs” of French-language and, more generally, European literature between continental Europe and English-speaking countries. He has long been a regular contributor to the Times Literary Supplement, The Antioch Review (in which he writes the “Poetry Today” column), and other publications. His essays have been gathered in the three-volume Paths to Contemporary French Literature (2004, 2007, 2011), Into the Heart of European Poetry (2008), and A Little Tour through European Poetry (2015). These two latter collections cover modern verse and prose poetry from nearly all the European countries. In 2015, his translation of José-Flore Tappy’s poetry, Sheds: Collected Poems 1983-2013 was a finalist for the National Translation Award in Poetry from the American Literary Translators Association.

Additional Reading:

Searching For Cioran https://www.amazon.co.uk/Searching-Cioran-Ilinca-Zarifopol-Johnston/dp/toc/0253352673

The Anguishes of E.M. Cioran (essay) https://www.newcriterion.com/articles.cfm/The-anguishes-of-E-M--Cioran-5980

Thinking Against Oneself: Reflections on Cioran (essay) https://emcioranbr.wordpress.com/fortuna-critica/thinking-against-oneself/