Gerard Manley Hopkins: Early Environmentalist Poet

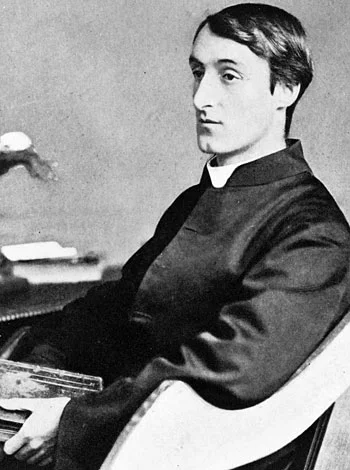

By Joseph J. Feeney, S.J.

The year is 1882, and Gerard Hopkins is walking on the grounds of Stonyhurst College, a Jesuit boarding school in rural Lancashire where he teaches. “Earth, sweet Earth,” he thinks, as he scans the rolling moors and fells of the River Ribble. “Sweet landscape,” he adds, then notices the thick leaves on his left and the grass at his feet. Suddenly he’s composing his environmental sonnet “Ribblesdale”:

Earth, sweet Earth, sweet landscape, with leavès throng

And louchèd low grass, heaven that dost appeal

To with no tongue to plead, no heart to feel;

That canst but only be, but dost that long--

Thou canst but be, but that thou well dost; strong

Thy plea with him who dealt, nay does now deal,

Thy lovely dale down thus and thus bids reel

Thy river. . .

After calling Earth and landscape “sweet,” he searches for the right adjective for the thick leaves and sprawling grass, and uses local dialect to make his poem specific: Lancashire’s adjectival use of “throng” (“crowded”)--the “leavès throng”—and (with humor) the Scots-English “louched” (“slouching”) for the grass. Clearly, he’s enjoying his “sweet” surroundings, even its slouching, lazy blades of grass.

Sweet, too, for the Jesuit priest, is the thought of how earth and landscape praise God by their very existence. They have “no tongue to plead” in prayer or “no heart to feel” love for God, yet earth, landscape, trees, even grass still praise God by just being: “Thou canst but be, but that thou well dost.” And over the ages their creating God continues to spread “Thy lovely dale down thus and thus bids reel / Thy river,” the word “reel” humorously making God a fisherman who “reels out” the winding River Ribble. To this point, the sonnet is happy, even whimsical, in image and language.

But then Hopkins thinks downriver to the textile mills and industrial plants of Preston, a boomtown of the Industrial Revolution and model for Dickens’ “Coketown,” and remembers the nearer factory towns of Blackburn and Burnley. As the octave ends, the poem darkens: through greedy humans, God “o’er gives all to rack or wrong.” In the sestet, Hopkins moralizes about human selfishness which “reaves” (plunders, robs) the earth, cutting down trees, paving the earth, and so ignoring future environmental consequences for the “world after” that Earth itself frowns:

And what is Earth’s eye, tongue, or heart else, where

Else, but in dear and dogged man? Ah, the heir

To his selfbent so bound, so tied to his turn,

To thriftless reave both our rich round world bare

And none reck of world after, this bids wear

Earth brows of such care, care and dear concern.

Such is the once “sweet” earth near Stonyhurst College, and such is the grief of Hopkins, an early and eloquent environmentalist poet.

Hopkins, then, is both an “early” and an “environmentalist” poet. To see him as “early” needs but a few words, for he may be the first environmentalist poet. His Romantic predecessors--Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, Keats--prized nature, but did not foresee its destruction or feel an obligation to preserve it. Hopkins, coming later (1844-89), recognizes nature’s fragility, sees its destruction, and stands with such early environmentalists as John Ruskin and William Morris in England, and Henry David Thoreau and John Muir in America. A scholar of literary ecology, England’s John Parham, even calls Hopkins “the one Victorian poet who consistently, imaginatively, re-created the specific conditions of the Victorian ecosystem.”

Establishing Hopkins as “environmentalist” is more complex, needing both careful definition and study of his poems. In his landmark work The Environmental Imagination, Lawrence Buell of Harvard defines “an Environmental Text” in terms of four qualities: (1) the nonhuman environment is not merely a “framing device” but suggests “that human history is implicated in natural history,” (2) human interest is not “the only legitimate interest,” (3) human responsibility to the environment is an ethical issue, and (4) a “sense of the environment as a process rather than a given...is at least implicit.” Summarizing Buell’s definition, I understand an “environmentalist” writer as one who feels an active interaction between the writer and the environment, with an ethical responsibility. Thus, I see “Environmental Hopkins” as a poet who (I) cherishes, (II) grieves for, and (III) seeks to preserve the environment.

I: Cherishing the Environment

What aspects of nature did Hopkins cherish? Often, it was its traditional beauty. A lovely nature-moment is in his poem “The Starlight Night,” written in Wales in 1877, when he looks up to the dark sky and sees not stars but “fire-folk,” towns, castles, diamond-quarries, and elves. He’s rapturous:

Look at the stars! look, look up at the skies!

O look at all the fire-folk sitting in the air!

The bright boroughs, the circle-citadels there!

Down in dim woods the diamond delves! the elves’-eyes!

His ecstatic joy brings dashingly original metaphors: stars as little “fire-folk,” as bright towns and round castles, as diamond-quarries, as sparkling eyes of mischievous sprites. An environmentalist surely begins with love, and Hopkins was an extraordinary lover of nature. No wonder the sonnet has sixteen exclamation points. In “The Wreck of the Deutschland,” he even blows a kiss to the stars: “I kiss my hand / To the stars, lovely-asunder / Starlight.” Ah, rare Hopkins!

Hopkins cherishes even nature’s “ugly” things: Lancashire’s “louchèd grass,” Oxford’s “weeds and waters,” England’s “weedy wilderness,” Scotland’s “weeds and the wilderness,” and Welsh “weeds, in wheels,” which “shoot long and lovely and lush.” He celebrates mud, too: muddy rivers--“the burling Barrow brown” and “a candycoloured,...gluegold-brown / Marbled river, boisterously beautiful”--and a mudpuddle in “Heraclitean Fire” which gradually hardens into footprints: the wind “in pool and rutpeel parches / Squandering ooze to squeezed dough, crust, dust; stanches, starches / Squadroned masks and manmarks... / Footfretted in it.” Such “ugliness” appears most directly in Hopkins’ beloved curtal sonnet “Pied Beauty” which celebrates cow-like skies, spotted trout, cracked-open chestnuts, black-and-white finches’ wings, rural fields, and common tradesmen and their gear: “All things counter, original, spare, strange; / Whatever is fickle, frecklèd.”

Hopkins particularly enjoys trees and birds: ashboughs, poplars, and elms; seagulls, peacocks, doves, and cuckoos. In his poem “The Woodlark” he even becomes a bird, first listening to the bird, then flying with it, finally chirping just like the woodlark. He listens: “Teevo cheevo cheevio chee: / O where, what can thát be?” Then he flies along, looking down: “‘the corn is corded..., / The ear in milk, lush the sash, / And crush-silk poppies aflash, / The blood-gush blade-gash / Flame-rash rudred / Bud shelling....’” Finally he becomes the chirping bird: “‘To the nest’s nook I balance and buoy / With a sweet joy of a sweet joy, / Sweet, of a sweet, of a sweet joy / Of a sweet--a sweet--sweet--joy.’” Tweeting like a bird, Hopkins surely became an active part of his environment.

Hopkins also offers three distinctive ways of cherishing his environment: perspective, shape, and selfhood. His perspective is psychological: in 1871 he notes that he was looking at clouds and thought, “What you look hard at seems to look hard at you....[and] I looked long up at it [the cloud] till the tall height and the beauty of the scaping--regularly curled knots...--had strongly grown on me.” Those eleven words--”What you look hard at seems to look hard at you”--epitomize Buell’s desire for “an active interaction between the writer and the environment.” Moreover, Hopkins’ love of nature’s attends to nature’s shapes. His poem “Moonrise June 19 1876” catches a new moon’s crescent-shape in homey images: a shape “dwindled and thinned to the fringe of a fingernail held to the candle,” or skin sliced from a fruit before eating it--a “paring of paradisáïcal fruit.” He notes the shape of raindrops in a pool--“water-roundels looped together / That lace the face of Penmaen Pool”--and the shape of “weeds, in wheels.” “Heraclitean Fire” catches the windblown shadow-shapes of elm branches on a white wall: “Shivelights and shadowtackle in long lashes lace, lance, and pair.” And describing drying mud, he uses the architectural word “fret” to describe the shape of footprints in the mud: “Squadroned masks and manmarks... / Footfretted in it.” Hopkins’ third distinctive approach is his sense that even a thing has selfhood. He derives this idea, of course, from human selfhood, but changes it radically in his poem “As kingfishers catch fire.” Beginning with birds and insects--kingfishers and dragonflies--he clearly asserts the selfhood of “each” thing: “that being [which] indoors each one dwells.” In the octave, which deserves quotation in full, after beginning with kingfishers and dragonflies, he offers other examples of non-human individuality, then in lines 5 to 8 draws a broad, philosophical conclusion about selfhood:

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame,

As tumbled over rims in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell’s

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves--goes its self; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying What I do is me: for that I came.

His assertion is extraordinary: not only humans, not only “mortal” things like birds and flies, but even non-living things like stones, violin-strings, and a bell’s clapper have selfhood: inside “each one” is a “being”--a unique, distinctive being--that “goes its self” and “speaks and spells” “myself.” In all its actions and in its very purpose, every being that exists cries out, “What I do is me: for that I came.” That is one of the strongest assertion of non-human selfhood ever made, and surely the assertion of an environmentalist willing to associate his very own selfhood with the selfhood of each bit of the world around him.

II: Grieving for the Environment

Hopkins also grieved for environmental destruction--an ethical response--in criticizing ugly railways and cities, lost trees and grass, and polluted air. “The Wreck of the Deutschland” records a trainwreck caused by a defective “flange and...rail.” “The Sea and the Skylark” calls the Irish Sea resort of Rhyl a “shallow and frail town,” and “Duns Scotus’s Oxford” deplores the University’s “base and brickish skirt”--ugly 19th-century brick houses and factories surrounding Oxford’s medieval heart of greystone gothic colleges.

Two poems lament the pollution of earth and air. “Binsey Poplars: felled 1879” records the cutting-down of an avenue of poplars upriver from Oxford in the village of Binsey. Its third line echoing the rhythmic thud of axes, the poem begins,

My aspens dear, whose airy cages quelled,

Quelled or quenched in leaves the leaping sun,

Áll félled, félled, are áll félled. . .

A thoughtful, grieving Hopkins continues,

Ó if we but knéw whát we do

Whén we delve or hew—

Háck and rack the growing green!

As a result,

Áfter-comers cannot guess the beauty been.

Tén or twélve, ónly ten or twelve

Strókes of havoc únsélves

The sweet especial scene,

Rúral scene, a rural scene,

Swéet especial rural scene.

In that lament, I add, Hopkins laments not only the loss of “beauty” but also the loss of selfhood: the axe-strokes “únsélve” this distinctive “rural scene” of Binsey.

Hopkins’ other critique of pollution is his well known sonnet “God’s Grandeur,” a different and richer sonnet when read from an environmental perspective. Its second quatrain records the dire effects of the Industrial Revolution on earth and air: with factories, “all is...bleared, smeared, with toil; / And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell.” Trade has “seared” the earth, and “the soil / Is bare now,” stripped of trees and grass. Humans have lost the pleasure of walking and playing on grass: “nor can foot feel, being shod.” And the sunrise horizon has lost its color: no longer golden, rose, or orange, “morning ... springs” now “at the brown brink eastward.” Such pollution also has an ethical dimension, for humans have disobeyed God’s command to care for the earth: “Why do men then now not reck his rod?”

Yet human pollution and destruction do not remove God’s presence in, and care for, his lovely world: despite pollution, “nature is never spent; / There lives the dearest freshness deep down things.” In a stunning, unexpected conclusion, Hopkins explains the underlying reason for environmental hope: “morning” still “springs-- / Because the Holy Ghost over the bent / World broods”--broods like a mother-dove--“with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.” The climax is entrancing: combining Holy Ghost, protecting dove, and morning’s “spring” over the horizon, Hopkins turns the first light-rays into the wings of the dove-Holy-Ghost, then with an astonished “ah!” ends his troubled sonnet with surprised confidence that God still protects his world despite human pollution--“nature is never spent /.../ Because the Holy Ghost over the bent / World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.” With this sudden turn, Hopkins’ critique of pollution and destruction ends on a note of environmental hope and, with God’s help, preservation.

III: Preserving the Environment

For the preservationist Hopkins, I turn to two gently hopeful poems, “Binsey Poplars” and “Inversnaid.” Near its end, “Binsey Poplars” turns from the lost beauty of the “aspens dear” to a wistful hope, as Hopkins pleads for preservation of “The sweet especial scene, / Rúral scene, a rural scene, / Swéet especial rural scene.” The ending is gentle, and lovely.

More explicit is Hopkins’ rich Scottish poem “Inversnaid,” about a waterfall on Loch Lomond. Walking upstream from the falls and its tourists, Hopkins passes the brownish pools of the “brook” (he uses the Scots word “burn”), then goes to its upper reaches, the narrow banks (the Scots “braes”) near its source. He describes first the falls: “This dárksome búrn, hórseback brówn, / His rollrock highroad roaring down” which “Flutes and low to the lake falls home.” Upstream, he finds “the broth / Of a póol so pítchblack, féll-frówning, / It rounds and rounds Despair to drowning.” Then, at its source,

Degged with dew, dappled with dew

Are the groins of the braes that the brook treads through,

Wiry heathpacks, flitches of fern,

And the beadbonny ash that sits over the burn.

With affection, Hopkins uses the architectural term “groins” to describe the shape of the arching trees, then Scots dialect--”burn,” “brae,” “beadbonny”--to give “Inversnaid” a local “self.” (The poem is best appreciated when performed with a Scots accent!) The last stanza brings Hopkins’ heartfelt environmental plea:

What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet,

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

Hopkins’ eloquent plea is at once majestic and, yes, near-comic, for it combines the traditional coronation-salute--“Long Live the King”--with a countryside affection for “the weeds and the wilderness.” This pairing of royalty and “weeds,” this use of a coronation cry to preserve “the weeds and the wilderness,” is Hopkins’ most vivid, passionate, and memorable environmental outcry. Surely “Inversnaid” confirms Hopkins as an early environmentalist poet devoted to this brook, devoted to nature, and sensitive to its shape (“groins”) and to its Scottish self (“burn,” “braes,” “beadbonny”). In his plea for preservation, “O let them be left, wildness and wet, / Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet,” Hopkins experiences, and helps us experience, an “active interaction between the writer and his environment, with an ethical responsibility”--the very essence of an environmentalist imagination and an environmentalist poet.

Long live Hopkins, the early environmentalist poet.