Hiding In Plain Sight: Writing From The Shadows

*Image courtesy of Samantha Anderson

By Scott Edward Anderson

“People always ask where poems come from,” Erica Jong wrote in an essay about her poem, “The Buddha in the Womb.” “And the truth is not even the poet knows. Especially not the poet.”

“Maybe you need to write a poem about grace,” Robert Hass begins his poem, “Faint Music.” It's curious that this opening line stands alone, as if not really part of the poem; rather, an exercise instruction the poet set out for him or an unattributed epigraph.

“Faint Music” isn't exactly a poem about grace, although there are moments of grace therein. It is a poem about the end of a relationship. In this case, the relationship of a friend, who contemplated suicide after “His girlfriend left him.” (Perhaps the grace in the poem is that he doesn't.)

He climbed onto the jumping girder of the bridge,

the bay side, a blue, lucid afternoon.

And in the salt air he thought about the word “seafood,”

that there was something faintly ridiculous about it.

No one said “landfood.” He thought it was degrading to the rainbow perch

he’d reeled in gleaming from the cliffs, the black rockbass,

scales like polished carbon, in beds of kelp

along the coast—and he realized that the reason for the word

was crabs, or mussels, clams. Otherwise

the restaurants could just put “fish” up on their signs,

and when he woke—he’d slept for hours, curled up

on the girder like a child—the sun was going down

and he felt a little better, and afraid. He put on the jacket

he’d used for a pillow, climbed over the railing

carefully, and drove home to an empty house.

We see this story not only from the perspective of the poet’s friend but, later, from that of the girlfriend who, with her new lover, is feeling remorse over how much she put into trying to make her earlier relationship work, “'I tried so hard,' sobbing now, 'I really tried so hard.'“

But then it shifts again and we see that Nick, the friend of the narrator, now identified, has been imagining this scene, projecting even, as perhaps the poet is projecting about his own new love.

“Faint Music” ends,

It’s not the story though, not the friend

leaning toward you, saying “And then I realized—,”

which is the part of stories one never quite believes.

I had the idea that the world’s so full of pain

it must sometimes make a kind of singing.

And that the sequence helps, as much as order helps—

First an ego, and then pain, and then the singing.

“One of the deep paradoxes in the history of marriage,” Hass writes in his introduction to Into the Garden: A Wedding Anthology, is “that the freedom to marry was established by the freedom to divorce.” He’s writing about Milton's “pamphlet making the plausible argument that people who could not love each other were compelled not to separate and to be faithful to each other, it amounted to treating marriage as stock breeding.”

Hass concludes, “If human love was holy, [Milton] argued, and if the individual soul mattered, people had to be free to find a mate who shared their heart's affections.”

***

Sometimes poets write so explicitly that they reveal more about themselves than more “confessional” poets. Don Paterson writes about what we keep in the cellars of our mind in his brilliant poem, “The Lie,” which appeared in his collection, Rain.

The speaker of the poem “nurtures” a suppressed self-deception, which he keeps chained and gagged in the basement, for fear it will escape and reveal itself.

As was my custom, I’d risen a full hour

before the house had woken to make sure

that everything was in order with The Lie,

his drip changed and his shackles all secure.

The anonymous blogger, “An American in the Cotswolds,” has an interesting take on this poem, which stuck with her after hearing Paterson read it in London.

She “interpreted ‘The Lie’ as being about [Paterson’s] own divorce. The boy to whom he tends so faithfully and yet from whom he has remained detached for ‘thirteen years or more’ is any one of the number of small lies in our relationships, lies that somehow culminate in that one big lie, that everything is just fine.”

Unable to answer The Lie’s questions, the narrator gagged him again,

and put it back as tight as it would tie

and locked the door and locked the door and locked the door.

D.H. Lawrence recommended we trust the tale not the teller.

***

A couple of years ago, as I was pulling together the poems for my book, Fallow Field, I looked at the title poem from a new angle. I’d recently been divorced and had some curious reactions to the poem reading it in that light.

My poem “Fallow Field” concerns a woman who leaves her failing marriage, packing her whole life into a small grip, “portable, where once there'd been permanence,” and disappearing into the tall grass.

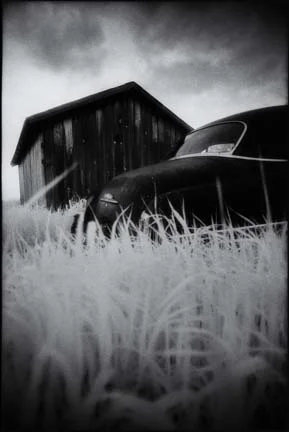

*Image courtesy of Joshua Sheldon

Writing that poem felt like a gift, a vision that came to me. In the summer of 1994, I was in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York with one of my closest friends, the photographer Joshua Sheldon, researching my book, Walks in Nature’s Empire.

As we drove out of the mountains, I saw something that made me stop. We turned around, pulled up near a dilapidated old barn with an old car parked next to it in the tall grass. Joshua crawled around in the grass, capturing what has become for me an iconic image. (I later used the photograph for the book cover.)

I sat in the grass until the poem started coming to me, until I received it. Or so I thought.

All these years later, after my marriage ended, I began to realize the poem was not about some found story received from outside, but came from deep within me. It was uncovering my shadow side.

When the poem was written I'd been having some doubts about my marriage and my own happiness. I'd fallen in love out of marriage and, although that love was never consummated, it gave me pause about what I was doing in and outside the marriage.

They call this grass

“poverty grain,” and there’s

no small comfort in the fact

that it’s as tolerant

of poor soils

as she was of her marriage.

In effect, I had used the narrative of the woman as a beard for my own feelings of isolation.

Lawrence Raab in his essay “Elegiac Problems,” writes that “a poem is a way of ordering memory, of revising it, even of inventing it.”

Was I revising or revisiting memory through the poem? Was I revealing more about my true feelings through the protagonist? (She appears dispassionate as she packs her belongings.)

Or was my poem merely, “a questioning,” to borrow Miller Williams's phrase for it, “a way of saying, ' we don't have the whole story,' or ' we may not have been looking at this in the right light…'“?

***

Sometimes poems speak from the darkest recesses of our minds and hearts. They reveal the shadow stories we tell ourselves and the deep-seated (seeded?) emotions that we hide from our conscious selves.

“Poetry begins in trivial metaphors, pretty metaphors, 'grace' metaphors, and goes on to the profoundest thinking that we have,” Robert Frost explained. “Poetry provides the one permissible way of saying one thing and meaning another.”

What the narrators in Hass’s and Paterson’s poems reveal about the poets is arguable -- perhaps they weren’t writing about themselves at all – but I suspect that as in my poem, they were, however unconsciously.

Perhaps the persona of the poem is a separate self, created by and distinct from the poet. Or perhaps it is the poet-self, crying out of the darkness and shadows, struggling toward the light, while simultaneously hiding in plain sight.

A Note About the Author: Scott Edward Anderson is the author of FALLOW FIELD (Aldrich Press, 2013) and WALKS IN NATURE'S EMPIRE (The Countryman Press, 1995). He has been a Concordia Fellow at the Millay Colony for the Arts and received the Nebraska Review Award.