Whitman & the Sea

by Scott Edward Anderson

In 1899, when my great-grandfather, Nathan Lewis Burgess, was ten years old, he sailed out of New Bedford as a cabin boy aboard the Bark Sunbeam, a whaling ship, bound for Newfoundland. Grandpa Burgess was legendary, in my mind, as were his stories and the multitude of blue-black ink tattoos he wore, souvenirs from his life at sea aboard the Sunbeam, the Greyhound, and other ships, including “square-riggers and tramp steamers,” as he told The Sun Chronicle, which published a profile of him on 21 October 1977. He made “three trips around the Horn,” the reporter writes.

My first long poem, which, thankfully, does not survive, was an “epic” imagining of Grandpa Burgess’s life as a whaler, heavily influenced by equal doses of Melville, Longfellow, and Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” All I can recall of the poem is a line that read something like, “The sea is dark; the ship goes up and down/ making the shipmates long for solid ground…” (Yikes…!)

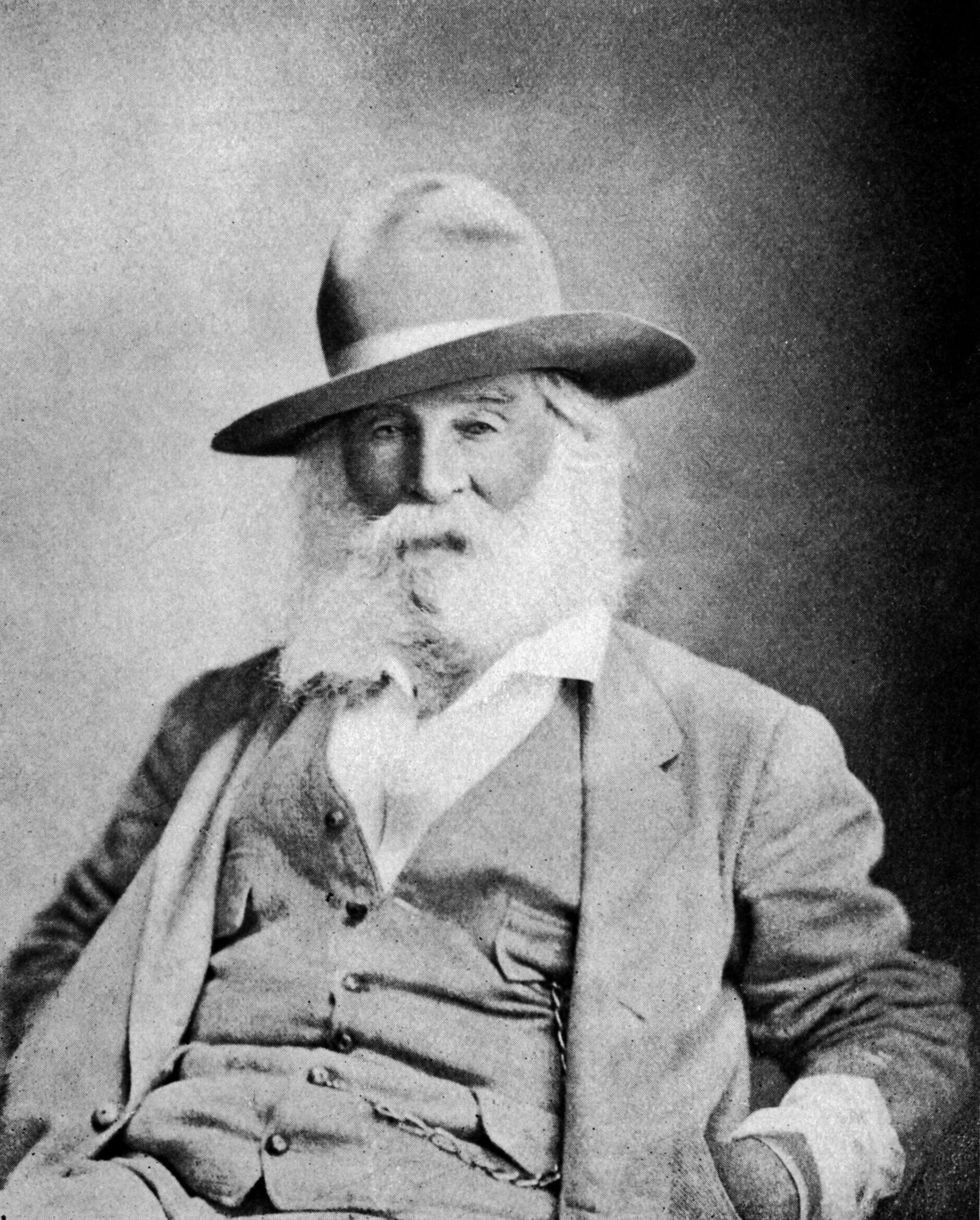

Another early influence was the great American poet—some would say the first truly American poet—Walt Whitman. I started writing poetry at age nine, encouraged by my surrogate Aunt Gladys, who plied me with poets and poetry to read up until her death at age 83 in 1986; Scottish poet Robert Burns was a favorite of hers and she was especially fond of Whitman.

At school the year I turned nine, I had to recite a poem and chose “O Captain, My Captain,” Whitman’s homage to the assassinated President Lincoln veiled in sea-faring analogy:

O Captain! my Captain! our fearful trip is done,

The ship has weather’d every rack, the prize we sought is won,

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring;

But O heart! heart! heart!

O the bleeding drops of red,

Where on the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

In his Preface to the 1855 (first) edition of his book Leaves of Grass, Whitman wrote, “The great poets are also to be known by the absence in them of tricks and by the justification of perfect personal candor. Then folks echo a new cheap joy and a divine voice leaping from their brains: How beautiful is candor! All faults may be forgiven of him who has perfect candor.” Whitman’s famous candor, exemplified by his “Song of Myself,” often masks the fact that he was also an excellent naturalist, especially of the sea and the seashore.

Whitman grew up on Long Island and, although he never embarked on an ocean voyage, he enjoyed sailing in a small boat around Peconic Bay out to Shelter Island and Montauk Point. Whitman’s family had settled on Long Island in the 17th Century and there may have been some seafaring tradition in his ancestry, which contributed to his fascination with the ocean and its occupations. Despite never venturing out to sea himself, his work is full of salt spray and sea water. His disciple, the naturalist and writer John Burroughs, wrote of Whitman’s work, “No phase of nature seems to have impressed him so deeply as the sea, or recurs so often in his poems.” Whitman’s observations of the natural world are scientifically precise, while maintaining a strong poetic sensibility; he encouraged Burroughs to develop a literature of nature that would aspire to those twin ideals. He did.

Late in life, Whitman told his friend and one of his first biographers, Horace Traubel, who wrote a multi-volume account of the last four years of the poet’s life in Camden, New Jersey, that his work as a poet is essentially that of a poet of the ocean. I’m not sure he meant to be literal there but looking at his poem “The World Below the Brine,” with its undulating, wave-like lines, teeming with the life of the sea, I can begin to sense that perhaps he was onto something:

The world below the brine,

Forests at the bottom of the sea, the branches and leaves,

Sea-lettuce, vast lichens, strange flowers and seeds, the thick tangle,

openings, and pink turf,

Different colors, pale gray and green, purple, white, and gold, the

play of light through the water,

Dumb swimmers there among the rocks, coral, gluten, grass, rushes,

and the aliment of the swimmers,

Sluggish existences grazing there suspended, or slowly crawling

close to the bottom,

The sperm-whale at the surface blowing air and spray, or disporting

with his flukes,

The leaden-eyed shark, the walrus, the turtle, the hairy sea-leopard,

and the sting-ray,

Passions there, wars, pursuits, tribes, sight in those ocean-depths,

breathing that thick-breathing air, as so many do,

The change thence to the sight here, and to the subtle air breathed

by beings like us who walk this sphere,

The change onward from ours to that of beings who walk other

spheres.

***

When I became serious about writing poetry around the age of fifteen, my mother gave me a Signet Classic paperback of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, with its dreadful cover illustration of Whitman, based upon the famous George C. Cox photograph from 1887. I still have it. Leafing through it now, I note the dog-eared pages and markings made in my teenage, budding-poet years. There’s this section from “Song of Myself”:

Houses and rooms are full of perfumes, the shelves are crowded

with perfumes,

I breathe the fragrance myself and know it and like it,

The distillation would intoxicate me also, but I shall not let it.

The atmosphere is not a perfume, it has no taste of the distillation,

it is odorless,

It is for my mouth forever, I am in love with it,

I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised and

naked,

I am mad for it to be in contact with me.

A dried leaf or flower marks the page for “Song of the Open Road,” which begins:

Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road,

Healthy, free, the world before me,

The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.

I also dog-eared the poem quoted above, “The World Below the Brine,” as well as “In Paths Untrodden” and “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” this last of which—another homage to Lincoln—remains a favorite among his poems today. I marked in pencil this stanza:

In the dooryard fronting an old farm-house near the white-wash’d palings,

Stands the lilac-bush tall-growing with heart-shaped leaves of rich green,

With many a pointed blossom rising delicate, with the perfume strong I love,

With every leaf a miracle—and from this bush in the dooryard,

With delicate-color’d blossoms and heart-shaped leaves of rich green,

A sprig with its flower I break.

Lilacs are plentiful in Rochester, New York, where I lived at the time, attending high school in a nearby suburb. There was a Lilac Festival each May, and I would go there with my post-hippie friends. We loved the heady mix of lilacs and grass—both the grass of Whitman’s title and the kind we might partake of on a spring day at the time; its pungent scent mingling with the “perfume strong” we loved, as Whitman did. Those were heady days.

***

This year marks Whitman’s 200th anniversary; he was born on 31 May 1819, near Hempstead, Long Island, not far from Cold Spring Harbor, and beyond that, Long Island Sound. The year of his birth, 1819, was an auspicious one for science and sea travel: Admiral William Edward Parry poked through the Northwest Passage, as far as longitude 112°51' W in the Arctic Ocean, the first to do so; Captain William Smith of the H. M. S. Williams discovered Desolation Island in the Antarctic; and the S. S. Savannah became the first steamship to cross the Atlantic. Back on land, G. B. Greenough published his influential treatise, A critical examination of the first principles of geology in a series of essays, and Johann Georg Tralles observed the “Great Comet of 1819,” known as C/1819 N1 or “Comet Tralles.”

Along with Whitman, American poets Julia Ward Howe and James Russell Lowell were born that year, as well as Queen Victoria and, born on the same day as Whitman, William Mayo, the English-American physician and chemist whose medical practice later gave birth to the Mayo Clinic. Kind of a star-studded birth year.

***

The text of the Signet Classic paperback of Leaves of Grass is modeled on the so-called “Death-Bed” edition, which was published in 1892, the year Whitman died and, coincidentally, the year my Portuguese great-grandmother, Anna Rodrigues Casquilho, was born on São Miguel in the Azores. She would sail to America fourteen years later aboard the S.S. Peninsular, arriving in New York Harbor in March 1906.

On the back-cover of this Signet Classic the copy reads, “Singer, thinker, visionary and citizen extraordinary, this was Walt Whitman. Thoreau called Whitman ‘probably the greatest democrat that ever lived’ and Emerson judged Leaves of Grass as ‘the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom America has yet contributed.’”

In “A Song of Joys,” Whitman writes an account of a whaling voyage,

O the whaleman’s joys! O I cruise my old cruise again!

I feel the ship’s motion under me, I feel the Atlantic breezes fan-

ning me,

I hear the cry again sent down from the mast-head, There—she

blows!

Again I spring up the rigging to look with the rest—we descend,

wild with excitement,

I leap in the lower’d boat, we row toward our prey where he lies,

We approach stealthy and silent, I see the mountainous mass,

lethargic, basking,

I see the harpooneer standing up, I see the weapon dart from his

vigorous arm;

O swift again far out in the ocean the wounded whale, settling,

running to windward, tows me,

Again I see him rise to breathe, we row close again,

I see a lance driven through his side, press’d deep, turn’d in

the wound,

Again we back off, I see him settle again, the life is leaving him

fast,

As he rises he spouts blood, I see him swim in circles narrower

and narrower, swiftly cutting the water—I see him die,

He gives one convulsive leap in the centre of the circle, and then

falls flat and still in the bloody foam.

My great-grandfather described a similar scene to Karen Zimmerly, a reporter for The Seekonk Star, in 1973:

As bo’man it was his job to keep the ropes straight after the harpoon was thrown. If the whale started to dive he had to cut the lines or else the little boat they were in would go under with the whale. However this wasn’t done until the last possible moment. It was a rather dangerous job but not, says Burgess, the worst. That was reserved for the man who had to first climb on the harpooned whale and start butchering it. As the first cuts drew blood which soon poured into the waters, schools of sharks would swim into the area. The sailor needed only to make one slip from his precarious position and he was soon gone to the sharks.

Zimmerly concluded, “Whale meat has, by the way, according to Burgess, a very gamey taste, similar to deer meat.”

***

Throughout his life, Whitman was fascinated by shipwrecks, a fascination that was common in his day, as greater numbers of people began traveling or working at sea in the 19th Century, and it was still a dangerous and risky proposition. In one of Traubel’s notes from a conversation with Whitman, he recounts the poet’s concern about a shipwreck, the Norwegian emigrant vessel S/S Danmark:

Friday, April 19, 1889

10.35 A.M. Marvellously clear out of doors—and the air mild as summer. W. sitting in his room by the open window, working on proof. Certain wrong insertions on lines. Asked me: “Isn’t it a remarkable day out-of-doors?” He thought it had that look. It inspires him to talk of the chair again. Bonsall and Buckwalter had advised Ed to get a proper chair and let them see about payment.

“And nothing of the Danmark,” said W.— “not a word! not a word!” If no sailing vessel had picked them up, then was “the whole story in”? “I do not quite understand this Azores business, though I suppose it is intelligible enough if one but knew”—the hope, viz., that the Azores would be the first point touched in case they had been picked up by a sailor. “There is one thing to be said of it—if they have gone down—if the whole crew—all the passengers—have simply been drowned—then is the final word spoken—then, as was the case in the Army when a man was killed outright—then need no sympathy be wasted on that. But if not—ah!” and his face assumed its serious aspect.

The Danmark was overwhelmed in a storm in the North Atlantic on 5 April, and later rescued by the S. S. Missouri, a cargo ship bound for Philadelphia from London. They first tried towing the Danmark, but the rough seas and ice made it difficult and the captain of the Missouri determined to head for the Azores, the nine-island archipelago to the south. But the Danmark continued to take on water, so the captain ordered his own crew to jettison their cargo and make room for the passengers and crew of the sinking ship. They finally made it to the island of São Miguel on 10 April 1889. (My great-grandfather, Nathan Burgess, was born 26 days later, on 6 May 1889 in New Bedford.)

Word didn’t travel fast in those days. On 13 April, another ship, the S. S. City of Chester, came across the Danmark and telegraphed to London. The Reuters News Service reported that the emigrant passenger ship had been seen adrift at sea without its life boats and with its anchor chains down. This is clearly what Whitman was reacting to, and perhaps to rumors of the aborted tow to the Azores. Finally, news of the rescue reached Whitman on the 22 of April, when he wrote to Richard Maurice Bucke:

The best news to-day is the saving of those 750 Danmark voyagers, wh’ quite gives additional glow to this fine weather—

Sixteen years earlier, in April 1873, he wrote to his mother, Louisa Van Velsor Whitman, of another wreck:

I see in the papers this morning an awful shipwreck yesterday night—seems to me the worst ever happened, a first-class, big steamship from England, went down almost instantly, 700 people lost, largely women & children, just as they got here, (towards Halifax)—what misery, to many thousand relatives & friends—

And in the version of his poem, “The Sleepers,” from the 1891-92 edition of Leaves, Whitman writes of a shipwreck where he imagines (or did he actually witness) having to “help pick up the dead and lay them in rows in a barn”:

The beach is cut by the razory ice-wind, the wreck-guns sound,

The tempest lulls, the moon comes floundering through the drifts.

I look where the ship helplessly heads end on, I hear the burst as

she strikes, I hear the howls of dismay, they grow fainter

and fainter.

I cannot aid with my wringing fingers,

I can but rush to the surf and let it drench me and freeze

upon me.

I search with the crowd, not one of the company is wash’d to us

alive,

In the morning I help pick up the dead and lay them in rows in

a barn.

In another poem from Leaves, “Song for All Seas, All Ships,” Whitman hails the ships and “all brave captains and all intrepid sailors and mates”:

Flaunt out O sea your separate flags of nations!

Flaunt out visible as ever the various ship-signals!

But do you reserve especially for yourself and for the soul of man

one flag above all the rest,

A spiritual woven signal for all nations, emblem of man elate above

death,

Token of all brave captains and all intrepid sailors and mates,

And all that went down doing their duty,

Reminiscent of them, twined from all intrepid captains young or old,

A pennant universal, subtly waving all time, o’er all brave sailors,

All seas, all ships.

He published this poem in the New York Daily Graphic of 4 April 1873, just a few days after the letter to his mother quoted above, in a slightly elongated version, under the title, “Sea Captains, Young or Old.” The poet had suffered a paralytic stroke early that year of 1873 and moved to Camden, where he spent his remaining days; his mother died in May.

Traubel recorded a note from Whitman, written on 2 July 1888, speaking about his own poetry, in which the poet claimed, “Its analogy is the Ocean. Its verses are the liquid, billowy waves, ever rising and falling, perhaps sunny and smooth, perhaps wild with storm, always moving, always alike in their nature as rolling waves, but hardly any two exactly alike in size or measure (meter), never having the sense of something finished and fixed, always suggesting something beyond.”

***

“Within a few months of producing his first edition of Leaves,” Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price recount in their biographical essay of the poet. “Whitman was already hard at work on the second edition. While in the first, he had given his long lines room to stretch across the page by printing the book on large paper, in the second edition he sacrificed the spacious pages and produced what he later called his ‘chunky fat book,’ his earliest attempt to create a pocket-size edition that would offer the reader what Whitman thought of as the ‘ideal pleasure’—‘to put a book in your pocket and [go] off to the seashore or the forest.’”

Whitman’s “ideal pleasure”—heading off on the open road for the forest or the seashore with a book of poems as one’s only companion—appealed to the fifteen-year-old, budding-poet me. I did just that later in the year with this Signet Classic paperback in my backpack: first, heading down to Whitman’s “Mannahatta” with my friend, Doug, in 1979, then wandering all over the Finger Lakes, and walking up along the shores of Lake Ontario. I made plans to travel out to Alaska after reading John McPhee’s Coming Into the Country that summer, but those plans fell through.

A year later, Allen Ginsberg, our contemporary Whitman, whom I met at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project’s annual poetry marathon, suggested I come out to Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, but I moved to New York City instead and never looked back. Later, I roamed the world, from the cities of Europe to the wildlands of the western U. S., the rain forests of South America to the islands of Indonesia—the latter sailing on a live-aboard. My feet have traversed the foothills of the Indian Himalayas, the Adirondack peaks, and the Desert Southwest. In the mid-1990s, I hiked all over New York State, producing a book called Walks in Nature’s Empire. (I finally made it to Alaska in 1996; my oldest son, Jasper Burgess Anderson, was born there.)

***

In 1982, The Evening Times, published a profile of my great-grandfather, by then living in a retirement community with his wife of 67 years. “Burgess, 93, completes another of the nearly 17 laps he makes around the complex daily, the equivalent of five to seven miles. ‘I won’t stop as long as I can move,’ he says, and moves on. Burgess has always been a traveler.” The twin examples of Grandpa Burgess and “Uncle Walt” keep me moving throughout my life.

Today, I try to manage at least 10,000 steps (roughly four miles) each day and some days as many as six miles or 15,000 steps. Much of my walking these days takes place with my dog in Prospect Park, in Whitman’s Brooklyn, on the western end of Long Island (Paumanok, in his parlance). Perhaps I’m embodying Whitman’s words from the 1860 version of Leaves, where he writes about walking along the shore:

Miles walking, the sound of breaking waves the other

side of me,

Paumanok, there and then, as I thought the old

thought of likenesses,

These you presented to me, you fish-shaped island,

As I wended the shores I know,

As I walked with that eternal self of me, seeking

types.

As I wend the shores I know not,

As I listen to the dirge, the voices of men and women

wrecked,

As I inhale the impalpable breezes that set in

upon me,

As the ocean so mysterious rolls toward me closer

and closer,

At once I find, the least thing that belongs to me, or

that I see or touch, I know not;

I, too, but signify, at the utmost, a little washed-up

drift,

A few sands and dead leaves to gather,

Gather, and merge myself as part of the sands and

drift.

About the Author: Scott Edward Anderson is the author of Falling Up: A Memoir of Second Chances (out this month from Homebound Publications), Dwelling: an ecopoem (Shanti Arts, 2018), Fallow Field (Aldrich Press, 2013), and Walks in Nature’s Empire (The Countryman Press, 1996). He has been a Concordia Fellow at the Millay Colony for the Arts and received the Nebraska Review Award.