Revisiting Emerson: Why His Ideas on Genius and the Everyday Image Matter Now

By Brian Fanelli

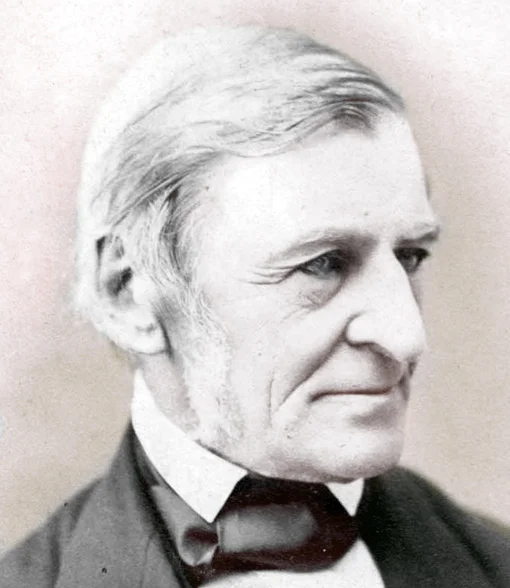

This fall semester, when I introduced the Transcendentalist writers to my American Literature students, I asked them how many heard of Ralph Waldo Emerson, causing one or two to raise their hands, while the rest shrugged or slouched in their seats. As soon as Henry David Thoreau was mentioned, however, several students stated that they at least heard of him. One asked, “Isn’t he the dude who lived in the woods for a while?” The general survey I took in my class this fall had the same result as the last few times I conducted it in the same manner. Thoreau still occupies the American imagination more than his counterparts, and after the 2016 presidential election, Thoreau’s status may only grow, especially his views expressed in “Civil Disobedience.” That said, as America enters an uncertain period, against a backdrop of a dangerous, growing nationalism in Europe, specifically Brexit, the rise of the anti-immigrant AfD Party in Germany, and Marine Le Pen’s similar National Front Party in France, and as we continue to question what it means to be American in the age of Trump and the alt-right/white supremacist movements, Emerson’s ideas are worth revisiting, especially his theories on individuality, imitation, genius, poetry, and forging a new American way.

I understand the attraction to Thoreau. His two-year stay at Walden Pond and his ability to build his own house and grow his own food will always have a romantic appeal. This romanticism was echoed in Jon Krakauer’s best-selling book, Into the Wild, which explores the plight of Christopher McCandless, a twenty-something Thoreau reader who trekked into the Alaskan wilderness and died, possibly by eating a poisonous plant. The 2007 film adaptation, directed by Sean Penn, lionized McCandless even more, and thus, Thoreau. There are scenes in the film in which McCandless, played by Emile Hirsch, paces back and forth in a rusted school bus, his only refuge in the wild, quoting sections from Walden. Yet, Thoreau never meant for the Walden experiment to be permanent. In fact, his cabin at Walden Pond was built on land Emerson owned, and he did have visits from Emerson and other friends. Even McCandless didn’t plan to make his break from society permanent. He tried to leave the Alaskan wilderness, but the thaw swelled a nearby river, making his passage back to mainland more difficult, trapping him in the woods for a longer period and ultimately dooming him.

Walden may be considered Thoreau’s masterpiece, and it certainly has attracted the most followers, but “Civil Disobedience” is more appropriate for the age of Occupy, Black Lives Matter, Trumpism, and European nationalism. It is an essay that has been hailed by conservatives and liberals alike for its statements on government, much like Thomas Paine’s early writings. It’s easy to see why Republicans would praise aspects of the essay, which begins, “I heartily accept the motto, ‘The government is best which governs least.’” Small government is the core philosophy behind modern conservativism. Yet, a few paragraphs later, Thoreau backtracks and admits that he is not calling for the abolition of government, but rather at once “a better government.” Thoreau never defines what that government looks like, however. The rest of the essay defends his decision not to pay the poll tax and face a night in jail, in opposition to slavery and the Mexican-American War.

In an age increasingly defined by protest, there are ideas in “Civil Disobedience” that are important to consider. Thoreau’s views on voting are especially interesting, especially particularly as the U.S. has another debate about the purpose of the Electoral College, after Hillary Clinton’s popular vote total well-surpassed that of Trump’s, rekindling conversations that echo the 2000 Bush V. Gore fiasco. Though he never encourages citizens not to vote, he is fully aware that in a republic or democracy, his vote doesn’t hold a lot of weight. Thoreau focused more on the idea of raising consciousness as a means to affect change, and this idea influenced leaders that followed, most notably Gandhi and Dr. King. Thoreau goes so far as to urge government workers to resign from their jobs as a means to protest war and slavery. He also has harsh words for those who sit on the sidelines in times of moral crisis. He states, “There are thousands in opinion opposed to slavery and to war, who yet in effect do nothing to put an end to them; who, esteeming themselves children of Washington and Franklin, sit down with their hands in their pockets, and say that they know not what to do, and do nothing.” This critique is similar to the written lashing in “Common Sense” and “The Crisis no. 1” that Thomas Paine gave to colonists who refused to support the Revolutionaries against British occupation. Thoreau believed that creating any type of change had to come through direct action, and as the American and European left figures out how to respond to the mainstreaming of anti-immigrant and white supremacist movements, such as the alt-right, it is wise to consider Thoreau’s words, especially his point that making government more representative of the people and being active must involve more than voting.

It is true that Emerson’s essays and lectures are not always easy to read, especially notably when compared to Thoreau’s work. Emerson primarily drew from his journals, so his lectures and essays contained great leaps of thought, sometimes within a few paragraphs. It is also true that some of Emerson’s ideas don’t hold today, but his statements on imitation, genius, and the American voice are increasingly relevant.

There are aspects of Emerson’s writing that can be dismissed, especially in an era when fewer and fewer Americans read at least one book per year and are sometimes suckered by fake news stories on social media. In his quest to preach no imitation and develop a distinctly American voice, Emerson cautioned against “book-learned” culture, especially foremost in his lecture “The American Scholar,” but also in “Self-Reliance.” Of literature and tradition, Emerson states in “The American Scholar,” “Meek young men grew up in libraries, believing it their duty to accept the views which Cicero, which Locke, which Bacon have given, forgetful that Cicero, Locke, and Bacon were only young men in libraries when they wrote those books. Hence, instead of Man Thinking, we have the bookworm.” This idea is echoed in “Self-Reliance,” when Emerson stresses again and again that one’s inner-genius can only be cultivated by reacting against tradition and society and listening to one’s inner-voice. This idea is understandable for the 19th Century, when Emerson and other American writers, especially his mentee, Walt Whitman, were trying to create a literature with a distinctly American voice. While Emerson’s thinking fit the time, in the context of creating a distinct American literature, his diatribes against the “book-learned” class can be dangerous today, especially for younger writers. Taken too lightly, without historical context, Emerson’s comments about bookworms can breed anti-intellectualism.

Furthermore, some of Emerson’s writing can come across as isolationist. For paragraphs in “Self-Reliance,” he rails against travel, calling it a “fool’s paradise.” He goes on to write, “The intellect is a vagabond, and the universal system of education fosters restlessness. Our minds travel when our bodies are forced to stay at home.” Again, some of Emerson’s views about travel are a reaction to American writers and artists who wanted to imitate European traditions and forms. Emerson wanted a break from European traditions, but in a globalized world, and in light of criticism by global citizens that Americans are too ignorant of other cultures, taking Emerson’s words to heart can have a negative effect. It would behoove Americans at this point in our history to better understand other cultures. An unwillingness to do so can lead to an uninformed citizenry, quick to elect leaders who would rather saber-rattle, or withdraw from the world, rather than listen and understand. In another essay, Emerson takes a different stance. In “Art,” Emerson admits, “the new in art is always formed out of the old,” indicating that you can’t create an American voice without a clear understanding of tradition and other countries. He also makes several references to art he viewed in Italy, but because “Self-Reliance” is his most well-known and most-taught work, his ideas presented in it about travel have broader scope.

Emerson is also not without his fair share of his contemporary critics. In his essay “Defence of Poetry 1997,” Charles Simic says, “Poetry for Emerson, Whitman, Dickinson, and so many others, is the process through which ideas are tested, dramatized, made both a personal and a cosmic issue.” He adds, “American poetry’s dizzying ambition to answer all the major philosophical and theological questions is unparalleled.” He then jokes about the idea of being able to see angels and truth in a blade of grass. Simic’s criticism is not without merit. Sometimes a blade of grass is merely a blade of grass, and there is no need to attach any spirituality or special meaning to it, but the idea that anything can be subject matter for poetry, an idea expressed in Emerson’s writing, and later reflected in William Carlos Williams’ poetry, manifestos and frequent criticism of T.S. Eliot’s reliance on classical literature references, traditional forms, especially in his later poems, and British citizenship, is especially of great import today. The idea that everyday images can make a poem takes poetry out of the academic halls and opens it up to more people. So yes, American poetry, at least in the strain of Emerson, Whitman, Dickinson, and Williams, may have a dizzying ambition, but at least it brings more people into the fold.

In the age of the M.F.A. program and poetry journals that only publish one school of thought, such as the New York School, there is another core Emersonian idea that has increasing relevance today, the idea of no imitation. In the opening of “Self-Reliance,” Emerson writes, “To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart, is true for all men—that is genius.” Right now, it is unclear where American poetry is going. There are too many clusters of schools and too many poets willing to stick to one particular style, be it an imitation of John Ashbery, or an imitation of Lowell, Plath, Sexton, and the other Confessionalists. I doubt that Emerson would like poetry journals that publish only one school of thought or M.F.A. programs that are out of reach economically for many people. Right now, poetry needs to regain its relevance in American culture. It needs to do something new.

With that said, Emerson’s idea expressed in “The Poet” that poetry is composed of “meter-making arguments,” meaning subject matter takes precedent over form, can be problematic, especially if the poem lacks musicality. Dana Gioia expressed this concern in his essay “Can Poetry Matter?” by noting that contemporary American poetry is too far removed from its musical roots and has thus lost readers. Still, though, there is something to be said regarding Emerson’s idea of genius. If poetry is ever going to find prominence again, it can’t be stuck in certain schools and prominent M.F.A. programs. Otherwise, it will never move forward or attract more readers. We are also in a period of history in which we desperately need poets to occupy a larger space in our culture and be a voice of dissent. Ginsberg’s reaction to 1950s conservatism and McCarthyism is an example. His anti-war activism and push for civil rights in the 1960s is another. Adrienne Rich’s criticism of unfettered capitalism or gender constructs is another example. Thoreau and Emerson’s outspokenness about the effects of the Industrial Revolution also comes to mind. All of these figures were public intellectuals with wider readerships than most of the poets on the scene today.

Since Emerson’s 19th Century writings and lectures, American literature has found its voice and has been canonized, thus some of Emerson’s statements, namely about travel and “book-learned” culture, are not as relevant. Yet, several of his ideas, especially regarding genius and finding truth and beauty in the everyday image, are increasingly important and, if applied, can help poetry to find a broader, larger audience again. Thoreau will continue to capture the American imagination. He will continue to be seen as the ultimate rebel and outsider, and his ideas in “Civil Disobedience” deserve to be studied again, especially as global protests continue. In Emerson’s writings, however, there are clues how to make poetry relevant again and how to avoid imitation. In an increasingly unstable America that needs its artists, Emerson deserves to be revisited.

A Note About the Author: Brian Fanelli’s most recent book is Waiting for the Dead to Speak (NYQ Books). His work has been published by The Los Angeles Times, World Literature Today, The Paterson Literary Review, Verse Daily, Main Street Rag, and elsewhere. Brian has an M.F.A. from Wilkes University and a Ph.D. from Binghamton University. Currently, he teaches at Lackawanna College.